|

|

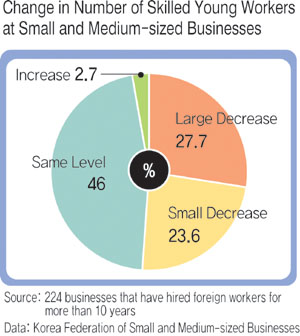

Number of skilled young workers

|

Low wages lead to loss of young domestic workforce

A South Korean electronics company, which once enjoyed a boom in the 1990s when it developed a device allowing customers to automatically turn on and off the signboards in front of their stores, recently gave up developing its own technology. While outsourcing development and design, the company is now just focusing on assembling. At the company’s plant in Seoul’s Seongsu-dong, the number of workers has been reduced to about 20 from a number once more than 50. Currently, most of the workers are either migrant workers or former Korean housewives. Packaging products alongside his employees, president Kim Jong-do, 55, said, "We have no more workforce available to teach to use precision machines, and were are lagging behind China in terms of technology. We halted facility upgrades and sustained our status quo by hiring foreign workers." Song Eun-seok, 33, is a manager of Changshin Precision Industry Co., an injection molding company. Though Song is the only son of the company’s president, he has no plan to inherit the company from his father. "Amid no new investment, a vicious cycle is propagating itself, because there are no technicians and foreign workers are harder to train," Song said, referring to a number of factors including the language barrier, level of education, prior experience, and cost of training versus average length of stay of foreign workers, currently only around three years."In the 1990s, companies in the Seongsu-dong area had focused on hiring foreign workers and housewives as orders surged," Song remembered. Roh Hee-seon, 57, who joined the company in 1995, said, "Compared with the past, there is a stricter line between technically skilled jobs and ordinary jobs. Only workers in their 40s and 50s handle machines." As South Korea is marking its 14th year of government initiatives to introduce foreign workers, the nation is having the difficulty of supplying a technical workforce to small and medium-sized manufacturers. Fortysomethings are now regarded as young workers. In early 1990s, high-school graduates used to begin their careers at plants in Seongsu-dong, but now only migrant workers and housewives fill the vacancies. The remaining middle-aged technicians accuse foreign workers of undermining the technical competitiveness of the small and medium-sized manufacturing businesses. The problem is not confined to Seongsu-dong. In a survey conducted by The Hankyoreh and the Korea Federation of Small and Medium-sized Businesses on Aug. 27, 54.7 percent of the 224 companies that have hired foreign workers for more than 10 years said that the "ageing of the South Korean workforce accelerated after the introduction of foreign workers." Only 24.7 percent said that the average age of their employees had dropped. Given the facts in Seongsu-dong, the system of encouraging companies to hire foreign workers is raising new questions. Fourteen years ago, the system was introduced to help local companies that were struggling to find new workers. However, the system has encouraged employers to keep wages low by allowing them to hire less costly foreign labor; it has also led companies to fail to nurture skilled workers. It is difficult for employers to justify teaching skills to foreign workers when they generally stay in South Korea for only about three years. Making the situation more dire is the fact that Chinese manufacturers are catching up with South Korean rivals with their enormous pool of inexpensive labor. All of these factors serve as a threat to small and medium-sized Korean manufacturers. Kwon Young-nam, executive vice president of Sungjin Electronic Parts Industry Co., a maker of car audio and remote control parts, said, "While our customers demand higher quality, our workforce is diminishing. The mobile phone industry has already collapsed and the auto industry is expected to sustain [its competitiveness] only over the next 10 years." Kwon added, "If we could go back to 10 years ago, we might not have hired foreign workers." A 45-year-old manager at a local dye company said, "When foreign workers were employed for the first time, company presidents welcomed the system because they were paid a monthly salary of about 400,000 won without insurance." But the low wages resulted in complaints from Korean workers, who moved elsewhere for employment and did not return, meaning that Korean companies "failed to secure their footholds for growth," the manager said. At the manager’s dye company, middle-aged Korean technicians and foreign workers handle high-pressure dyeing machines, while workers in their sixties and housewives carry supplies and package products. Although migrant workers have relieved the worker shortage once felt by manufacturers, experts point out the system has prompted young Korean workers from shunning manufacturing jobs because they perceive the jobs as ’only for foreign workers.’ Korea Industrial Research Institute researcher Cho Young-sam said, "Supplying cheaper workers with the government’s funding eventually became a poison for small and medium-sized manufacturers. [Companies that use] basic machinery operations such as coating, cutting, and molding are facing crises," Cho said. Korea Labor Research Institute researcher Lee Kyu-yong said, "Amid growing concerns about shortage in skilled workers, it’s time to think about countermeasures." The influx of foreign workers accelerated in 1993 after the government introduced an industrial training system to help small and medium-sized companies deal with a shortage of workers. However, the system will be abolished by the end of this year due to side effects such as illegal hiring, corruption, and human rights abuses. Instead of the system, foreign workers are currently hired under an "employment allowance system," which was introduced in August 2004. The system, though with more rigorous rules, in fact has made it easier for employers to hire foreign workers. About 61,700 foreign workers entered South Korea this year under the system. As of 2005, the Ministry of Justice said the number of foreign workers in South Korea was estimated at about 346,000. Among them, the number of illegal foreign workers stood at an estimated 181,000.