|

|

Freelance reporter Geoffrey Cain, who authored a book on Samsung that is set to be published in February, speaks with a Hankyoreh reporter at an office in the Hannam neighborhood of Seoul on Nov. 21. “Patience was the “most important attribute for delving into Samsung,” he said. “None of the usual reporting techniques worked.” (by Kang Jae-hoon, staff photographer)

|

Geoffrey Cain’s book, which talks about the company’s growth and corporate culture, will be published in February

Back in 2009, when Geoffrey Cain first arrived in South Korea as the senior correspondent for GlobalPost, a US-based current affairs news website, he was planning to focus on the North Korean issue, like other foreign correspondents. But he changed his mind after a shocking visit to a Samsung workplace. “It was overflowing with banners praising Chairman Lee Kun-hee, and several senior executives were able to quote Lee’s speeches and sayings from memory. It almost made me think I was in North Korea,” Cain recalled. Cain’s experience on the ground at South Korea’s best-known global corporation has kept his attention fixed on South Korean society and on the Samsung issue in particular. “At first, it was hard to understand how the Lee family were treated like royalty by the South Korean media and why young South Koreans were competing so fiercely to get a job at Samsung,” he said. Since then, Cain has published numerous articles about Samsung both at GlobalPost and other media outlets, including Fast Company, an American business magazine. His reporting on the chaebol has put him in contact with over a thousand people, including scholars, employees at rival companies in South Korea and overseas, employees and executives at Samsung, and high-profile members of other chaebols linked to Samsung. In February of next year, Cain will be publishing a book spanning his research over this period, tentatively titled Samsung Empire. Before coming to South Korea, Cain was based in Cambodia, where he covered Asia for the Economist and the Far Eastern Economic Review. A series of investigative reports on labor issues in Cambodia was selected in 2015 as a finalist for a journalism award by the Society of Publishers in Asia. In 2015, Cain visited North Korea to report on North Korean society under the rule of Kim Jong-un. After about six years in South Korea, Cain has returned to the US, where he is working as a freelance reporter. During a brief trip to South Korea, Cain sat down with the Hankyoreh on Nov. 21 to talk about Samsung. Hankyoreh (Hani): Is there any particular reason you’re so interested in Samsung? Geoffrey Cain (Cain): South Korea achieved miraculous economic growth through what are known as the chaebols, but they also conceal a lot of problems. Samsung is a great example of the interplay of light and darkness in the Korean economy. It had plenty of reporting value. Hani: Did you actually meet members of the family that controls Samsung? Cain: I wasn’t able to meet Chairman Lee Kun-hee or Vice Chairman Lee Jae-yong. However, I did meet some of the key figures at chaebols linked to Samsung such as CJ, Hansol and Shinsegae. I tried my best not to contact them too frequently. I figured they weren’t likely to tell me anything approximating the truth. Young “Samsung men” view their employer with a proud yet critical eye Hani: What was it like meeting them in person? Were there any memorable episodes? Cain: It was striking to see them refer to themselves as the “royal family.” They often expressed pride at having deigned to play an important role in helping South Korea become an advanced economy. To understand Samsung, you have to study the kings of the Joseon dynasty, the zaibatsu dynasties of Japan, and even North Korea’s Kim dynasty. All their stories are fundamentally not that different from Samsung. Hani: I’m curious why you’re so critical of Samsung that you would compare it to North Korean society. Cain: I’m not being critical—I’m just saying they represent the same period of time. When Samsung started to grow in the 1960s and 1970s, South Korean society was similar in some ways to North Korea at the time. But with politics dominated by the military dictatorship of Park Chung-hee, a unique corporate culture formed in South Korea. A management style where everyone acts in line with orders from a single boss began to bleed over into companies as well. This militaristic approach remains in place at South Korea’s other chaebols, such as Hyundai, LG and Lotte. Cain went on to say that he is particularly impressed by the young “Samsung men,” a term encompassing both new recruits and middle managers at the group. He was once having a meal with Samsung employees when they told him about an athletic event the company used to host called the “Samsung Summer Festival,” which reminded them of North Korea’s mass games. “I remember I felt the same way about that,” Cain said. Given that, he still has trouble understanding how these employees remain so loyal to the company. Hani: What did you usually talk about when you met “Samsung men”? Cain: They had a mixture of pride about getting a job at Samsung and a critical stance on unacceptable behavior. It was a love-hate relationship with the company. They tended to respect Samsung for its team spirit, but disagree with the imperial management style by Chairman Lee and his family. Hani: You used the word “empire” in the title of the book. Cain: I wouldn’t have used that word if I had written a book about a company like Apple, Facebook or Uber. Those are typical companies that develop and manufacture products and promote and sell them to consumers. But Samsung has a narrative straight out of a thriller: dynastic management, a struggle for the throne and internal discord. If the internecine conflict in the popular American drama Game of Thrones actually existed, it probably wouldn’t be hard to find it in South Korea’s chaebols. Hani: Don’t some people think that’s an effective way to run a company? Cain: The loyalty of the "Samsung Man" was important in the 1980s. I will never forget the story I heard from a Samsung semiconductor engineer. In 1983, Samsung held a 64-kilometer march in the mountains all night long. The reason? To show their dedication to the cause of creating Samsung's first semiconductor, the 64K DRAM, to "suffer so we can succeed," he told me. This would be unthinkable in the US. It's this spirit that allowed Korea to overcome all odds and rise as a serious power. But this "chaebol culture" has its downsides. Hani: What kind of downsides do you mean? Cain: I saw a strange dichotomy. Samsung is a global leader in technology, but has also managed to preserve the old system of dynastic rule. Samsung wishes for everyone to see it as an excellent, sophisticated technology company. Isn’t that a contradiction? The nearly feudal loyalty of the “Samsung man” can only take it so far. There are also issues with how they deal with workers’ rights.

|

|

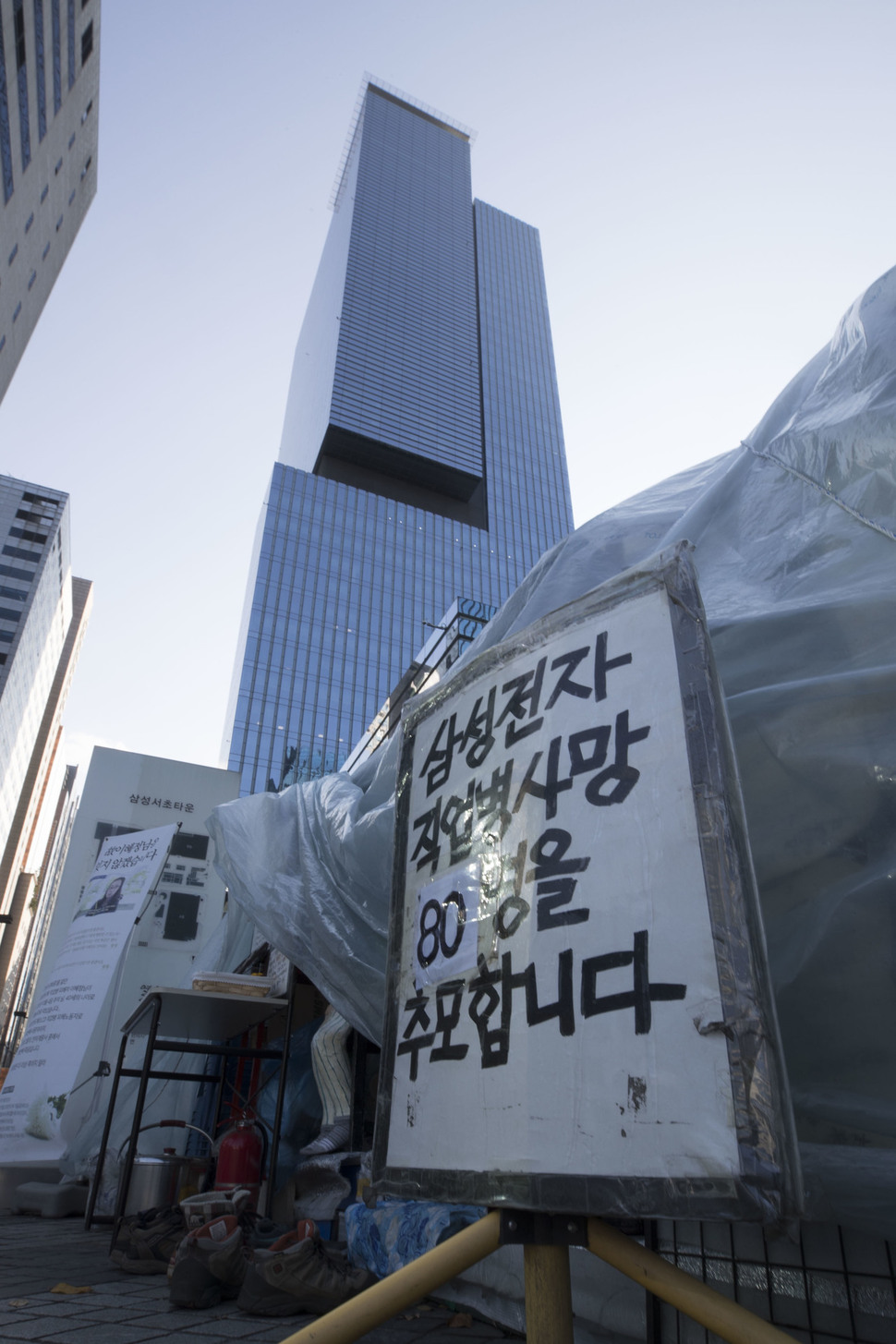

Members of the civic group Bannolim hold a sit-in outside the Samsung headquarters in the Seocho district of Seoul on Nov. 26 to demand that Samsung take steps to protect the health and rights of workers in the company’s semiconductor division. The sit-in has been going on for 782 consecutive days. (by Kim Seong-gwang, staff photographer)

|