|

|

Sungdong Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering in Tongyeong, South Gyeongsang Province, has suspended operations for over two years. (Kim Bong-gyu, staff photographer)

|

11 years later, banks have yet to face adequate punishment for devious financial practices

Eleven years have passed since Korea was sideswiped by the “KIKO incident,” harming many small and medium-sized exporters. Some had to liquidate assets; others defaulted on their loans and declared bankruptcy. There are also many companies that barely survived, but are still suffering lingering effects. Meanwhile, the banks that sold the monstrous KIKO (a currency derivative, short for “knock in, knock out”) to SMEs have never been punished.

In the meantime, the financial industry has instigated several other similar incidents, with different targets and at different times. One of the best examples is the recent controversy over derivative-linked securities and funds (DLS and DLF) tied to overseas interest rates that are expected to cost investors more than 1 trillion won (US$830.05 million) in losses. Almost the only difference between the two incidents is that the KIKO scandal affected SMEs while the DLS and DLF scandal is likely to cause major harm to individual investors.

This investigation into the KIKO incident, 11 years later, takes a close look at how small and medium-sized manufacturers were driven to ruin by cutting-edge financial techniques, raising questions about why finance exists in the first place.

|

|

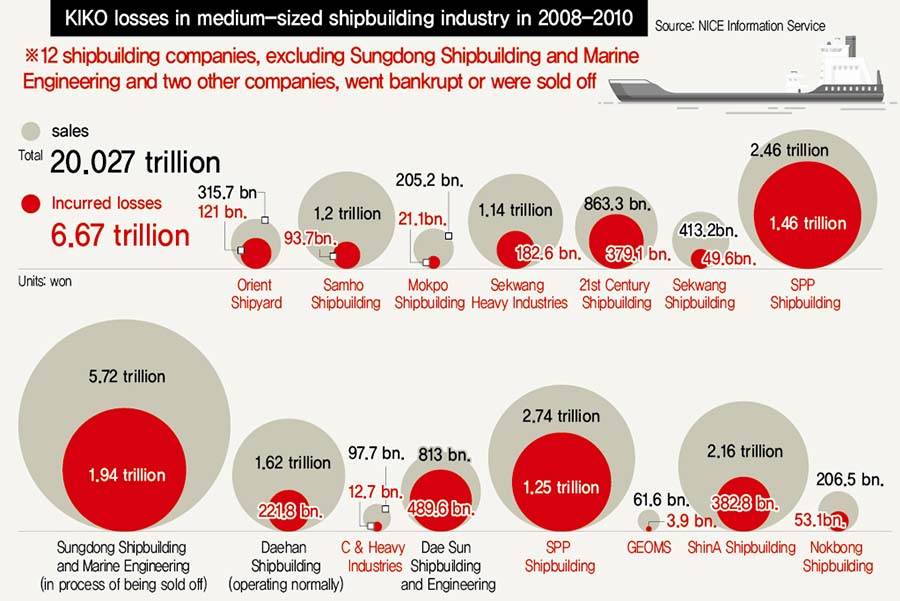

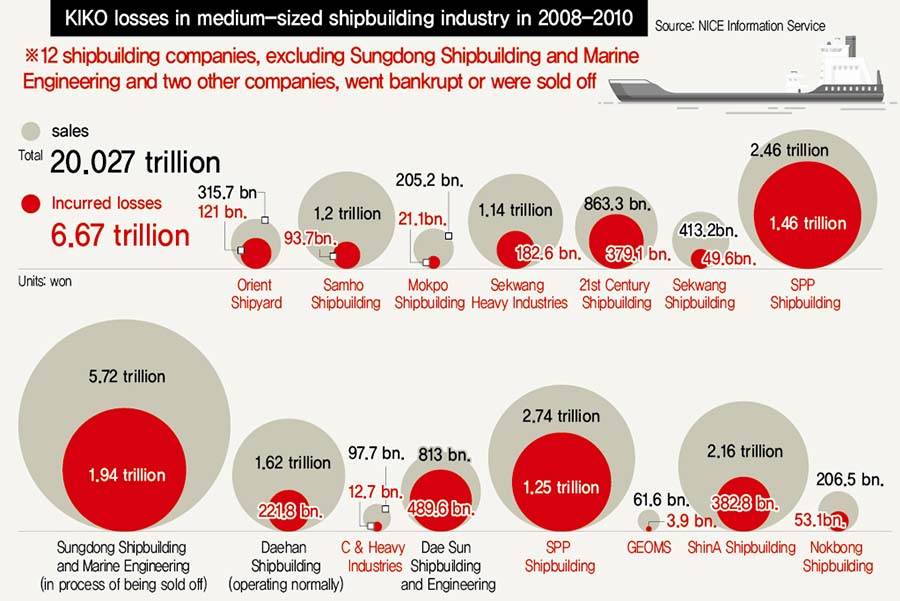

KIKO losses in medium-sized shipbuilding industry in 2008-2010

|

The fall of South Korea’s once dominant shipbuilding industry

“The saddest thing about the collapse of the mid-sized shipbuilding industry is that the 10,000-20,000-ton chemical tanker industry — of which Korea had held a 60% share — was entirely lost to Japan and China. That market used to be led by Korean companies like 21st Century Shipbuilding, Samho Shipbuilding, Sekwang Shipbuilding, and Nokbong Shipbuilding,” said Yang Jong-seok a senior analyst with the Overseas Economic Institute at the Export-Import Bank of Korea.

21st Century Shipbuilding and the other companies that Yang mentioned are all out of business today. The same is true of Shina SB and SPP Shipbuilding, which had dominated the market in 50,000-ton chemical tankers. Chemical tankers are ships designed to transport various kinds of chemicals, such as alcohol and ethyl. In the shipbuilding industry, tankers and bulk carriers above 10,000 tons are classified as mid-sized ships. Container ships with a capacity of above 1,000 TEU are sometimes added to this category as well. Most of the South Korean shipyards whose technical competitiveness had led the global mid-sized shipbuilding market have collapsed since 2008.

That year, the South Korean mid-sized shipbuilding sector came under assault from all directions, struck by an unexpected crisis. During the boom years of the early 2000s, some domestic shipyards had made bold facility investments and offered low prices while competing for bids. That was when several mid-sized shipyards set up operations in Tongyeong and Goseong County, both in South Gyeongsang Province. But such management techniques backfired when subprime mortgages in the US triggered the global financial crisis. The global shipbuilding industry saw demand dwindle, and Korean mid-sized shipyards were forced to keep churning out the ships they’d already agreed to make at cut-rate prices without any new orders coming in. Soon, those companies found it hard to secure financing.

|

|

Sungdong Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering in Tongyeong, South Gyeongsang Province, has suspended operations for over two years. (Kim Bong-gyu, staff photographer)

|

KIKO derivatives backfire due to dipping won-dollar exchange rate

It was at this point that South Korean shipyards suffered yet another blow: the KIKO incident. South Korean banks had been selling those derivatives to small and medium-sized exporters since 2007. The banks had created and sold KIKO to help companies hedge against the losses they would incur if the won-dollar exchange rate fell. But when the global financial crisis caused the exchange rate to rise instead, KIKO inflicted huge losses on those companies.

Because of their exports, shipbuilding companies were dollar rich, and they had a poor understanding of foreign exchange hedges and derivatives. That made them the prime target of the financial sector.

“Before filling out an order, shipbuilders have to receive a refund guarantee from a bank, and shipyards were often persuaded, if not coerced, into signing up for KIKO in exchange for receiving a refund guarantee (RG) from a bank. That’s why it was generally export-oriented mid-sized shipyards that were harmed in the KIKO incident, rather than chaebol affiliates such as Hyundai Heavy Industries and Samsung Heavy Industries,” said Han Sun-heung, a professor at the Maritime Systems Graduate School at KAIST. An RG is the certificate that a bank issues to a client that has paid the advance on a ship they’ve ordered, a precaution taken in case the shipyard goes under.

When the Hankyoreh investigated the 15 mid-sized shipyards that had enrolled in KIKO, it learned that 12 of them had already gone bankrupt or been liquidated. Quite a few of the shipyards, including 21st Century Shipbuilding, had declared bankruptcy, while a few, including Mokpo Shipbuilding, had gone into administration and been sold to other companies. As of September, only two of the shipbuilders — Daehan Shipbuilding and Daesun Shipbuilding — were still in business. Even these companies are getting fewer orders than they did during the shipbuilding boom of the 2000s.

KIKO (listed as derivatives on financial statements) inflicted massive losses on these 15 shipyards. The losses began to show up in company accounting in 2008, adding up to 6.67 trillion won (US$5.54 billion) at the 15 companies over the next three years. That’s nearly twice the 3 trillion won (US$2.49 billion) that South Korea’s Financial Supervisory Service (FSS) said that 738 (later 919) companies lost because of KIKO contracts in 2010. The glaring discrepancy reflects the serious shortcomings of the FSS’ investigation.

|

|

Moon Gui-ho, the former chairman of 21st Century Shipbuilding, which went bankrupt in in 2013

|

The tragic story of Sungdong Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering

Sungdong Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering is the classic example of a mid-sized shipyard devastated by the KIKO incident. As recently as 2008, Sungdong was ranked as the world’s eighth largest shipyard, based on its order backlog. Including subcontractors, a total of 12,000 people were working for the company.

While Sungdong had led the global mid-sized shipbuilding industry in the early 2000s, its collapse began with the KIKO incident. Figures available on the FSS website show that, between 2008 and 2010, Sungdong suffered around 2 trillion won (US$1.66 billion) in KIKO-related losses. While the company had managed to double its revenue three years in a row until 2009, when yearly sales first exceeded 2 trillion won, that wasn’t enough to make up for the KIKO losses.

In 2010, Sungdong eventually reached a voluntary workout arrangement with its creditors, including the Export-Import Bank of Korea, but it never managed to get back on its feet. Sources in the shipbuilding industry reported on Sept. 30 that a public sale of the company was about to begin — the fourth attempt to liquidate the company so far. If a new owner doesn’t emerge by the end of the year, Sungdong, which is currently in court receivership, will cease to exist.

“Currently, about 500 union members are holding out on unpaid leave. If no buyer appears, they’re all going to lose their jobs. If Sungdong gets a buyer, we’re ready to put everything on the table, including our wages and working conditions. We’re calling on the government and South Gyeongsang Province to take action,” said Kang Gi-seong, head of the Sungdong chapter of the Korean Metal Workers’ Union.

“Hidden champions” in midsized shipbuilding market fell to pieces in wake of KIKO incident

Something similar happened to SPP Shipbuilding. Established in 2002, SPP expanded rapidly through 2008 and acquired nine affiliates and subsidiaries, including SPP Shipbuilding and Maritime Engineering and SPP Shipping. In 2008 alone, the group made nearly 2 trillion won in sales. SPP had become the world’s 10th largest shipbuilder, controlling more than half of the global market for 50,000-ton medium-range tankers.

But when the shipbuilding industry went bust, SPP paid the price for its reckless investment. Of course, it might never have been forced to close its doors if it hadn’t faced more than 2 trillion won in KIKO losses (including those incurred at SPP Shipbuilding and Maritime Engineering) between 2008 and 2010.

The “hidden champions” in the midsized shipbuilding market — including Samho Shipbuilding, 21st Century Shipbuilding, and Shina SA (located in Tongyeong, South Gyeongsang Province, like Sungdong) — all fell to pieces in the wake of the KIKO incident, suffering between 93 and 380 billion won in KIKO losses. 21st Century Shipbuilding and Shina SB announced bankruptcy in 2013 and 2015, and Samho was sold to a company called Korea Yanase in 2013. The closure of these shipyards had a knock-on effect on the Tongyeong economy.

Ulsan’s Sekwang Heavy Industries, once a leading player in the global mid-sized tanker market, entered bankruptcy proceedings in 2012. Several mid-sized shipyards in Mokpo, South Jeolla Province, shut down as well. Between 2009 and 2017, C& Heavy Industries (sic), Sekwang Shipbuilding, and Mokpo Shipbuilding declared bankruptcy or were sold to other companies.

The KIKO-related downfall of shipyards led to a slowdown in the country’s mid-sized shipbuilding industry. According to statistics provided by the Export-Import Bank of Korea, domestic mid-sized shipbuilders only accounted for 4% of the global mid-sized shipbuilding market (in terms of compensated gross tonnage, or CGT) last year. That’s just a quarter of the level in 2007 (17.7%), before the KIKO incident. The value of orders at mid-sized shipbuilders has also plummeted over the same period, from US$26.21 billion in 2007 to US$1.21 billion in 2018.

|

|

Moon looks over where his company once operation in Tongyeong, South Gyeongsang Province.

|

Polarization also intensifying in shipbuilding industry

Mid-sized shipyards’ share of South Korea’s total shipbuilding industry has also declined. Last year, orders placed at mid-sized shipyards only accounted for 4.5% of the industry total, hardly comparable to the 27.5% figure reached in 2007. Considering that South Korea’s three big shipbuilders — namely, Hyundai Heavy Industries, Samsung Heavy Industries, and Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering — were once again ranked first in the global shipbuilding market for orders won, polarization is growing starker in the shipbuilding business, as in other areas of the economy.

The disintegration of South Korea’s mid-sized shipping industry has ended up benefiting China and Japan’s shipbuilding industries, which had been the Korean companies’ main competition. The two countries have rapidly filled the vacancy left by South Korea, thanks to robust financial backing from the Chinese government and Japan’s policy of keeping the yen weak since Shinzo Abe returned to the premiership there.

A report titled “The Importance of the Mid-Sized Shipbuilding Industry and Development Methods” that was published by the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) in December 2018 explains the industry’s importance as follows: “The significance of the mid-sized shipbuilding industry goes beyond local economies by defining the competitiveness of South Korea’s shipbuilding industry as a while, including the equipment and material industry and the industrial ecosystem. If South Korea abandons the mid-sized shipbuilding industry, rivals [such as China and Japan] won’t stop with dominating that industry but will continue to reinvest the profits gained there in efforts to challenge [South Korea] in building high value-added large ships. Indeed, signs of that can already be seen today.”

Need to rebuild mid-sized shipbuilding industry

In order to rebuild the mid-sized shipbuilding industry, there’s a critical need to help shipbuilders that were ruined by the KIKO incident to stabilize their operations or get a fresh start. Once again, the most serious obstacle here is finance. The commercial banks that convinced many shipbuilders to enroll in KIKO in exchange for issuing RG in 2007-2008 withdrew from the RG market altogether after the financial crisis. Critics describe this as the typical predatory behavior of banks, which lend umbrellas when the sun is shining but take them back when it starts to rain.

“Another problem with the financial sector is that it won’t even give the mid-sized shipbuilders that were forced to close because of their KIKO losses a chance to get back on their feet. Since nearly all the banks are to blame for the KIKO incident, they need to help competitive shipbuilders resume normal business operations by issuing RG and providing financial support,” said Kim Deuk-ui, president of the Financial Justice Alliance.

“The government also needs to set up appropriate standards for providing financial support to shipyards so as to prevent banks from refusing to issue RG by imposing arbitrary or excessively strict requirements,” Kim added.

By Choi Sung-jin, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]