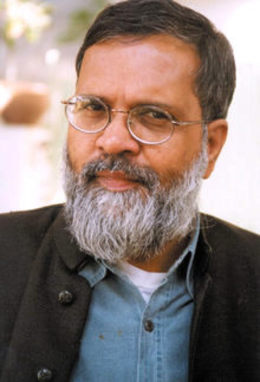

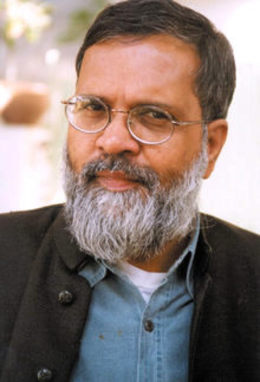

By Praful Bidwai, Columnist

There can be no two opinions about the imperative need to condemn the North Korean nuclear test strongly and unequivocally, as most of the world’s countries and peoples have done. But a problem arises with that small minority of countries that long ago did what North Korea did on October 9, and for equally questionable reasons: detonate a weapon of mass destruction that has the potential to kill tens of thousands of noncombatant civilians in an instant.

These countries are the United States, Russia, China, Britain, and France, recognised as nuclear weapons-states (NWSs) by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, as well as three others, which are known to have nuclear weapons - namely, Israel, India, and Pakistan.

There is also a problem, albeit a lesser one, with those countries, also numerically small, who accept the NWSs’ "nuclear umbrella". They, too, legitimize the idea of acquiring security through the ability to rain death and destruction upon an adversary’s unarmed civilians.

The problem is that the second group practices despicable double standards: preaching abstinence for non-members of the Nuclear Club while demanding that the Club’s members keep their weapons because they are "responsible" states. This robs its criticism of Pyongyang of logical consistency and moral authority.

That is one reason why the countless dire warnings issued to North Korea, especially by the U.S., against crossing the nuclear threshold, did not have the desired effect.

The warnings belong to the past. North Korea today is a de facto NWS. How should the world deal with this? Is this "reality" unalterable? Can South Korea learn to live with a nuclearized North? Should it do so by building a nuclear deterrent, or through peaceful negotiations?

Answers to these questions depend on two basic issues: one’s assessment of why the Pyongyang regime conducted the explosion; and second, assessing what real, practical options are available to the world in dealing with North Korea. Can Seoul persuade Pyongyang - whether through peaceful negotiations or military coercion - to adopt a course that generates greater security for all concerned in Northeast Asia?

On the first issue, it should be clear that North Korea did not commit an "act of lunacy" or a "madman number" on October 9. As its rulers saw it, the test was not meant just to salvage their own regime from toppling - the regime wasn’t and isn’t about to collapse. It was a largely rational, although dramatic and excessive, response to a "real and present" threat and an actually existing danger, one which has become greatly aggravated over the past year, after the U.S. imposed a harsh economic blockade on North Korea and froze all international bank transactions with it.

The history of Pyongyang’s nuclear-related insecurity goes back to the Korean War and General Douglas MacArthur’s plan to launch nuclear strikes on 26 targets in the North. The sustained rivalry the North has had with the U.S. and South Korean right since then has done little to relieve Pyongyang’s insecurity. Nor has Japan growing’s militarization. The Cold War has still not ended in Northeast Asia.

The only break in this long spell of insecurity came when the Clinton administration signed the Agreed Framework with Pyongyang in 1994. But even this relief evaporated when the U.S. reneged on its fuel-oil and light-water reactor commitments.

President George W. Bush’s demonization of North Korea as an "Axis of Evil" state carried a grave threat to North Korea. The patently unjust Iraq war, founded on lies about weapons of mass destruction, was a legitimate cause for insecurity and fear in Pyongyang. Bush himself has confessed to his "visceral" hatred for Kim Jong-il and repeatedly threatened to topple his regime.

North Korea’s threat perception wasn’t imaginary. And it became magnified, despite the Beijing denuclearisation agreement of September 2005, because Washington stressed this agreement’s Article I (committing North Korea to abandon its nuclear pursuits) to the exclusion of Article II (under which the U.S. and North Korea would "respect each other’s sovereignty, exist peacefully together and take steps to normalize relations").

It can of course be argued that nuclear weapons don’t really protect a nation; they are purely weapons of offense and mass annihilation, not defense. As a peace activist, I believe this. Nuclear weapons don’t give security. Period.

However, if North Korea is to be faulted for rejecting this logic and embracing the fallacy of deterrence, then so must the other eight NWSs. In fact, they can cause far greater damage with their nuclear weapons. Just two of them can destroy the world many times over.

The point is, the flawed security logic of security/deterrence can be turned on its head if the root causes of insecurity are addressed. This might represent one key to the Korean crisis.

North Korea offers a contrast to, say, India. India faced no true security threat in 1998. Its relations with its neighbors, including China and Pakistan, were improving, and its global economic weight rising. Its nuclear weapons pursuit was driven by a search for "prestige" and a place at the world’s High Table, not by security needs.

Unlike India, North Korea might be persuaded to give up its nuclear weapons if it is made to feel more secure. This can happen if the U.S. treats it as a state worthy of diplomatic relations despite its different socialpolitical system, appreciates its keenness to become a part of the international community, and engages it politically through bilateral talks. These talks must assure Pyongyang that Washington is not planning to destroy its regime.

The details of how Pyongyang might be made to feel more secure can be worked out. But the principle of addressing its insecurities and anxieties is all-important.

That brings us to the real options of dealing with North Korea. Conceptually, the world has only three: yet more sanctions, military force, or non-coercive diplomacy.

The U.S. has had operative sanctions against North Korea since 1950. These were partially relaxed after 1994, but have been tightened to the maximum possible extent. And yet, even the launching of an economic war on North Korea did not prevent it from going nuclear.

Barring perhaps a blanket ban on overseas travel by North Koreans - a draconian measure unworthy of support on elementary human rights grounds - sanctions cannot be further tightened much (although they can be broadened to other countries).

That apart, it is highly unlikely that China and Russia would go along with tough sanctions. Not only is Pyongyang adept at sanctions-busting, but its authoritarian regime is unconstrained by the magnitude of human suffering that sanctions might cause.

That brings us to military force. This is a fraught and dangerous option, if it is an option at all, on the Korean peninsula. About 37,500 U.S. troops are stationed in South Korea. North Korea’s 1.2 million-strong army, with 11,000 pieces of artillery and an arsenal of missiles, can make devastating conventional strikes against South Korea and even Japan, where another 40,000 U.S. troops are stationed. And now there is the risk of a nuclear attack.

Besides, the U.S. is too deeply caught up in the Iraq quagmire to be able to spare any troops for Northeast Asia.

Can South Korea become secure against a nuclearized North by developing nuclear weapons itself? The answer is no: the result will be a ruinous arms race and greater strategic instability in the peninsula.

We on the Indian subcontinent have seen how greatly nuclearization complicates strategic equations and adds tremendous uncertainty and instability to them. Neither India nor Pakistan can use military coercion against each other. Compellence - the idea of making your adversary do you will - simply does not work in this case.

Policymakers in South Asia, who thought of using nuclear coercion, made us pay a heavy price after the 1998 nuclear tests: a medium-scale armed conflict in Kashmir in 1999, an aircraft hijacking that brought Pakistan’s Taliban connections to the fore and fomented great suspicions in India, followed by a 10 months-long eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation in 2002, involving one million soldiers.

The Korean peninsula must not repeat the India-Pakistan blunder.

The third (diplomatic) option is the only real one. The U.S. and its partners in the six-party talks must try to dissuade North Korea from pursuing a weapons program by offering it security and economic incentives, including generous agricultural and industrial assistance and food and fuel aid.

This can be followed up with military confidence-building, including a verifiable halt to fissile production and other de-escalation measures in both Koreas. Such arrangements could lead to the creation of a Northeast Asian nuclear weapons-free zone, which would addresses the security concerns of all regional states.

Such a regional initiative must be tied to and become part of a larger global effort to reform the present nuclear order by honestly implementing the two-way bargain on which it was originally based. Under the bargain, the non-nuclear weapons-states agreed not to make or acquire nuclear weapons and subjected themselves to IAEA inspections. In return, the NWSs committed themselves to serious negotiations to eliminate nuclear weapons worldwide. However, the NWSs have cheated on their part of the bargain.

The remedy lies in negotiating a return to the global disarmament agenda. What we need is to take nuclear weapons worldwide off of "alert" status, to separate nuclear warheads from delivery vehicles, and to begin the phased destruction of nuclear armaments. It is only when nuclear weapons stop being a currency of power that further breakouts of this manner will cease.