|

|

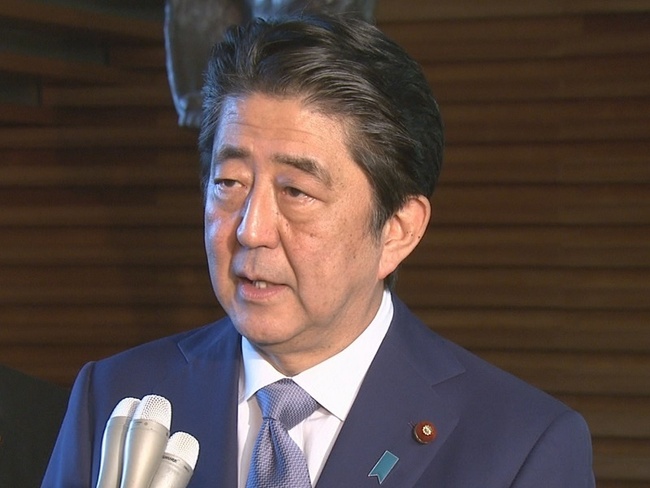

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe

|

Japanese prime minister’s speech before Japanese Diet came 2 days after Supreme Court decision

“The government is talking about the ‘issue of workers from the Korean Peninsula’ rather than ‘conscripted laborers.’ At the time, the National Mobilization Law’s National Service Draft Ordinance included terms for recruitment, government placement efforts, and conscription. In fact, the plaintiffs in this trial themselves said this was an issue of ‘Korean Peninsula workers,’ in that they said they had responded to recruitment.” Speaking before the Diet of Japan on Nov. 1, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said the Japanese government planned to use the term “workers from the Korean Peninsula” to refer to victims of forced mobilization, rather than the term “conscripted laborers” used in the past. This came two days after an Oct. 30 South Korean Supreme Court ruling ordering a Japanese business to pay compensation to victims of forced conscription. The Japanese government’s terminological tweak appears meant to downplay the forced conscription issue. Since Abe’s remarks, Tokyo has been removing all references to “conscripted laborers” from its documents. The Japanese ambassador also made reference to the “Korean Peninsula worker issue” in a briefing for Japanese businesses in South Korea held in Seoul on Nov. 15. Abe’s remarks appear to suggest that because a method of designating individuals for the issuance of conscription warrants was adopted in 1944, mobilization prior to that date was not coercive in nature. This merely muddies the waters of the forced mobilization issue: even mobilization through “recruitment” and “government placement” was essentially coercive, bearing the weight of the Government-General behind it. Accounts gathered by a truth commission on forced mobilization during the Japanese occupation show that even in cases of ostensible “recruitment,” various coercive strong-arm tactics were used with the backing of the Government-General’s administrative authority. The individuals mobilized also performed difficult labor under harsh oversight by Japanese businesses. Because of mandatory insurance and installment savings enrollment, they were not properly compensated. On that basis, the South Korean government has designated all individuals mobilized according to the National Mobilization Law as of 1938 as victims of forced mobilization. Even Japanese experts agreed that Abe’s remarks were incorrect. University of Tokyo professor Masaru Tonomura, who published a book titled “Forced Mobilization of Koreans,” posted a piece titled “Is the Term ‘Conscripted Labor’ Incorrect or Appropriate?” on his webpage on Nov. 6. “Prime Minister Abe has said that the South Korean plaintiffs who worked for Nippon Steel were not ‘conscripted laborers,’ which is clearly false,” Tonomura said. “While conscription is [generally] understood to have taken place according to National Service Draft Ordinance procedures, there were actually other ordinances [related to conscription],” he explained. “For instance, there were the munitions company conscription regulations implemented in Dec. 1944, which deemed all employees [already working] at designated munitions companies and factories to have been conscripted. Nippon Steel [now the Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal Corporation] also appears to have received this designation. In other words, the plaintiffs had already become ‘conscripted laborers’ by a certain point.” Tonomura went on to say that “not all of Japan’s wartime mobilization of Koreans was conscription according to the National Mobilization Law, nor did that [mobilization through other forms that National Mobilization Law conscription] result in damages that were more trivial.” “Differences are not really recognized when it comes to violence and coerciveness to acquire workers,” he said. “In that sense, it is not appropriate to refer to Koreans mobilized for wartime labor as ‘conscripted laborers’ either. It would be more apt to use the term ‘forced mobilization victims’ or ‘wartime mobilization victims,’ or simply ‘mobilization victims,’” he added. On Nov. 5, around 100 Japanese attorneys argued that the essence of the forced conscription issue was one of human rights violations. It is quite distressing to see the Abe administration’s attempts to blur the issue’s essence with what amounts to wordplay. By Cho Ki-weon, Tokyo correspondent Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]