|

|

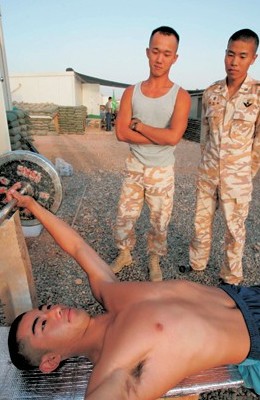

A group of Zaytun soldiers eats their rations.

|

Part 2 of 2 in a Hankyoreh 21 series

For South Korea, Vietnam and Iraq have something in common. In a span of 30 years, South Korean troops are again stationed where U.S. troops are stationed. Korea sent a total of 320,000 soldiers to Vietnam; it has now sent over 10,000 soldiers to another distant country.

Every year, thousands of Korean soldiers are sent to Iraq. Not everyone who applies can go there. To be selected, one needs to have a letter of agreement from one’s parents, a first-level physical evaluation, and the approval of the current unit’s commander. In addition to those factors, one needs to pass security clearance.

Only those who meet these requirements can go. Before departure, these select individuals also have to pass through a two-month special training to survive life in the desert.

The total number of Korean soldiers who have gone to Iraq has already reached 10,000. Since the first batch of Korean troops went there in August 2004, every six months 3,000 soldiers are rotated out and replaced by a new batch. This August, a new group left for the Middle East.

In an effort to better understand the experience of Korean troops in Iraq, Hankyoreh 21 met with some 30 Korean veterans who came back from Iraq, and also conducted an e-mail query with 100 of them. The official name for the company of Korean troops in Iraq is Zaytun, meaning "olive" in Arabic. This article includes testimonials of seven Zaytun veterans, whose tour of duty ranges from the first to the third batch.

"If you go there, you will have to pay the price for it."

"K" (worked in the administration division, August 2004~February 2005): While watching TV as a young kid, such as the series "Tour of Duty" or movies like "The Patriot," I came to hold a large admiration for soldiers, including their willingness to risk their lives for the sake of their friends. I wanted to be one of them. When my teacher asked me what I wanted to do in the future, I said proudly: "soldier." I even told my friends that I would ’protect’ them in case of war. I was young. I didn’t yet have a clear idea of what a "country" meant. I just thought that The Pledge of National Allegiance, The Silent Tribute for Patriotism in school, these all amounted to patriotism. I just believed what I was taught by teachers.

Later, I went to college, and as with all Korean men, I had to do my compulsory military service. Actually, it was a realization of my long-forgotten dream. Ironically though, I do well in the military. But the everyday routine and strict rules gradually oppressed my critical thinking. The sacred civil obligation of serving for the defense of the country actually transformed to an enforced submission of the draftees to authority in a classist society.

While I was serving my time in the military, the second Iraq War broke out. After some debate, South Korea decided to send troops as a sign of solidarity with the United States. With Iraq, I saw a way out. I wanted to get out of the suffocating routines at that time. Part of my motivation was to see what was going on in Iraq.

In the summer of 2004, there were many protesters at the military gate blocking our departure to Iraq. But we effortlessly got around them by taking helicopters in the early morning.

The town of Arbil, where Iraqi Kurds live, is also a stronghold for insurgents. There were often fights. But the place where we were was very quiet. We often heard shootings. But we were well insulated, by Kurd mercenaries that the Korean government hired to protect us. So, instead of fighting, we paid attention to taking care of flowers and collecting scorpions. Slowly, we began to forget the reason why we came to that conflict-ridden land in the first place.

I began to think, "Well, it really didn’t matter. Regardless of why we came this far, when we would go back to our country, there will be honor and recognition waiting for us." We also earned an extra US$1,809 per month for "putting our lives in danger." We, however, called ourselves mercenaries, although we weren’t sure about who our employer was. Would that be America? South Korea? Or a construction or oil company? We weren’t sure.

Sometimes, there were accidents. There was a soldier whose foot was cut off during the rushed construction of our barracks; there was a soldier who was accidentally zapped with electricity [due to faulty wiring] while grabbing the shower nozzle; there was an Iraqi contract laborer who died, paint covering his body, when a machine exploded during the painting process. There were some other casualties that were not reported outside.

In Iraq, I got see some famous people such as President Roh Moo-hyun, government ministers, and lawmakers who we used to see only on TV. They visited us and gave us some food and money. They hugged us and shook hands with us. They then reminded us why we came there. They told us that they were proud of us because we were contributing to world peace. But no one believed them. We only trusted ourselves and our friends there.

I heard that there were some who had begun to display mental disorders. However, these weren’t confirmed cases. They were just rumors. What was for sure was that no one was truly sane. As time went by, the Iraqi insurgents were no longer just enemies of the U.S. They became our enemies. My colleague in the same barracks confided to me that he developed a desire to kill people for the first time in his life when he was conducting a mission in which his troops moved from Kuwait to Arbil via Baghdad.

He worked as a driver. When his superior told him to "run over" anything that would get in the way, he doubted his ears. By the time when his convoy was passing through Baghdad, he saw bullets whizzing past and rockets exploding nearby. He became nervous but at the same time, he also started to feel a thrill. It was a strange sensation. He once again asked his superior, "Can I really run over anything that gets in the way?" His superior answered, "You bet, everything."

Gradually, we started to harbor hatred for the people of the land, people who we don’t know very well. We also didn’t know why we had begun to hate them. It was the same with the death of Kim Sun-il [the South Korean missionary who was kidnapped in Iraq and later beheaded]. We didn’t feel like it was the death of another human being. Rather, we worried more that we might not get to go to Iraq because of his death because of the growing public criticism about sending troops to Iraq.

But I don’t think it’s easy for someone to blame us for how we felt about the whole thing. We were also victims. I am not saying this as an excuse. But that’s how I really feel.

Many people in Iraq still believe that the Korean troops in Iraq are "locked" inside our own safe military camp. When I was in Kuwait, I met many allied troops from other countries. None of them said this war was right. They had started to leave.

The Korean troops don’t have a plan to do so yet. As a person who has been to Iraq, I want to tell anyone who wants to join the Zaytun unit that if your decision is because you are going through a tough time in the Korean military or bored to hell, you will have to go through a life a lot tougher and a lot more boring. If it’s for money, you’ll also pay for that, too.

"Many are killing time in Iraq."

"J" (Served in the engineering corps, March 2005~August 2005): Some people say "Why should we send troops to Iraq?" Those who were there don’t think this way at all. I was one of those who was of the mindset that said, "It’s okay to get killed in Iraq. If I am lucky enough to survive, then I would be able to do anything."

Ever since I came back from there, I’ve never had any negative feelings about my experience there. Actually, serving in Iraq was easier than serving in the Korean army. Surrounded by uncertainty, in Iraq we used to say, "It’s better not to know when we are going to die."

Of course, there was also stress. It’s lonely, tough out there. But then, it was still much better than in the Korean military. Those who had gone there ahead of me told me, "Come to Iraq. Things are cool here. And you make a decent amount of money, too." That was true for me, as well. Later, I didn’t even feel like coming back home.

However, I want to point out that there was also such a waste of manpower. As a person who got paid to go there, that was good. But from a taxpayer’s perspective, I also think that considerable money has gone down the drain. It costs a lot of money to send a person there, including salary, airline tickets, military gear, and other stuff necessary to live in the desert. The region where the Korean troops are stationed is relatively safe. But they are overprotected by Iraqi Kurds who are paid by the Korean government.

I think the number of engineering corps there is way too high, also. Unlike civilians tend to think, we are not there to build some big buildings. All we do there is get contracts and provide supervision. The civilian-military cooperation (CIMIC) then employs local supervisors, who then hire local workers. A Korean official from the engineering corps once a month goes to the sites and checks on the construction process. That’s all. The enlisted soldiers have nothing to do with all of this. That is a job for an officer. All the things that other Korean soldiers do for the local people is to help paint, repair electric lines, and other small things.

I was an officer. While I was there, for 6 months I got to go to the sites only a few times. Most mechanics at the Zaytun unit stay within the well-protected military compound. The majority of them never got to have the chance to get out. So, sometimes we even give them a reason to do so saying, "Since you came all the way to Iraq, maybe it’s also good to see how things are like outside."

The original purpose of sending Korean troops there was to rebuild Iraq. But we went there and spent most of our time in maintaining our own living facilities. We are too withdrawn and I think it’s problematic. The people high up in the ranks are so concerned about our safety. For them, a safe return is more important than accomplishing anything.

I don’t know how South Korea’s sending troops has contributed to the national interest. I get the feeling that we didn’t offer something really useful for Iraqis. We did so for the sake of our national image in the outside world. American soldiers in Korea enjoyed a good reputation in the past because they gave chewing gum and chocolates to the locals. Perhaps my government is thinking about something similar. Personally, I believe that if we had sent actual combat troops to Iraq, we would have gotten a lot better deal from the United States.

"Most are from poor family backgrounds"

"J" (assigned to the human resources division, August 2004~February 2005): I was in the human resources division. So, I got to see the files of people who had come to Iraq. About half of them are either from single-parent families or don’t have parents at all. Many of them said they applied because they had some financial problems. My parents were initially against my going to Iraq, too. People from poor families tended to be the majority of applicants. Demographically speaking, there should be more applicants from Seoul, where a quarter of the nation’s population is concentrated. But actually about 80 percent of them were from local provinces. In my battalion, there were only six people who were also attending college in Seoul.

"I would have gone mad if I hadn’t been comfortable there"

"K" (worked as a medic, March 2005~August 2005): While I was there, they took special attention to lessening our stress. They held some music concerts, volleyball and basketball games. And we often threw parties. The officers repeatedly emphasized, "You are the best of the best." I think the reason for all of this was because it would have been very hard to endure life there otherwise.

My life at Zaytun was more comfortable than the one I have in Korea, except for the hot weather and homesickness. Things can drive you crazy there. At Zaytun, they provide you with enough time for things such as eating meals and rest. If you do your given assignment, people don’t interfere with your life. The conditions in the barracks were much better than those in the Korean army. We had individual beds, personal drawers. The room was air conditioned and had a TV set. I played some Playstation games. They allowed us to have digital cameras and MP3 players. So, I often listened to music and watched Korean broadcasting programs on satellite. Some other units held classes for music, martial arts, and even a baking class.

"Another day, another 70 dollars!"

"O" (Served in special forces, March 2005~August 2005): I wanted to have a new experience. When I was there, I thought I would get much out of the experience. But the only thing I got out of it was money. Nothing else. We seldom were attacked. But once, a bomb explored near our post and some shrapnel was embedded in our equipment. But we were safe, because we were inside the compound. At first, I got nervous, and even scared. But then, things became normal again. Whenever we heard that there might be an attack, nothing would happen. I didn’t even put on my bulletproof vest anymore.

I was bored to death there. I think others felt the same. It was very stressful, having to see the same people every day for the six months I was there. We were not allowed to go out. It was so boring. Everyday we repeated the same routine. I joked to my colleagues there that "if we endure this boredom, we make $70 dollars anyway, every day."

When I first applied, I was of the mindset that, "It’s okay if they don’t pay me. The more important thing is that I get to have a new experience." But when I got there, and as the routine became prolonged, I was finding it difficult in finding the meaning of doing all of this. My only solace was getting paid and paid well.

When I was in the Korean military, we had different drills, routines, and education. But in Iraq, our routine was more limited in scope. Working, eating, working, eating, that was it. Even during the hours that we were supposed to have rest, they made us do repetitive chores. It was fatiguing, and sheer tedium. Since all of us were given real ammunition there, I thought about why they occupied us with something constantly, and my hunch was that perhaps this had to do with the fact that they didn’t want us to do something stupid with the real ammunition.

"Did we just come to dig for our country?"

"S" (worked as a driver, September 2005~March 2006): I got to see the Korean TV news PR material about Zaytun. They showed only the good things about it. The TV shot also included a part where we played with Iraqi children. But actually all I did was digging in the ground.

It seems the Korean media is also slowly forgetting about Zaytun. In the past, when we had a new replacement, there was at least a small bit of coverage in the newspaper. Not anymore. Actually, I am increasingly ignoring it. My memory about it is also fading. When someone asks me about how it was out there, I answer, "Well, nothing special. Not too dangerous. Kind of manageable."

Before I went there, I was full of expectations. The money was a big factor for me as well as the promise of having a 25-day vacation. However, when I was there, I felt like we were hardly doing anything meaningful. "Regardless of what we do here, there’s nothing good for my country," I thought. Actually, I didn’t think what I was doing was benefiting my country. Personally, I didn’t have a good experience there. After all, we only went there to make money.

"We fought over laundry."

"K" (worked in administration division, March 2005~August 2005): I applied to Zaytun to see how much I could push myself in an extreme situation. In a sense, it was a challenge for me. But when I got there, things were quite different from what I had expected. It wasn’t as dangerous as I had thought at all. The Korean newspapers said we went there to "help Iraq," to "safeguard peace." The truth was anything but what they said.

When you go there, you repeat the same routine every single day during your assigned six months. A day’s routine goes like this. You wake up at 7 in the morning, go to your office around 8 o’clock, have lunch at 11. And from noon to 3 p.m., you take a nap. It’s because it is too hot to do anything during those hours. You do one more hour of work until 4 p.m. And then, you are free for the rest of the day.

Then, about one month into my arrival, a rocket bomb explored near our compound. After the incident, our free time was reduced. From 4 p.m., instead of having free time, we had to prepare sandbags around the containers where we lived. There were hundreds of containers. That meant we had a lot of work to do. Worse, the sandbags often ruptured when exposed to the sun for an extended period of time. Then, we had to make more sandbags. We repeated the process over and over again. There, I had to do a lot of shoveling, which I hadn’t done in the Korean military.

Life was stressful enough. But we couldn’t go out. There was no way to let us. If any one of us were to be kidnapped, there would be a demand in South Korea for the withdrawal of Korean troops from Iraq. So, our commander wouldn’t let us leave the compound. Because we were confined to a limited space and under stress, there were often fights.

One of those involved laundry. A guy pulled someone else’s clothes out of dryer before the clothes were dry. They got into a fight and a person’s nose got broken. The hitter was later repatriated.

To relieve our stress, they organized some sports games, which didn’t receive very good responses. Participating in these events was stressful, too. They also did a survey about how we felt about our lives there. But it wasn’t anonymous. You had to write down your name and your ID number. Who would write truthfully under such a circumstance? I was naive. The first time I did it, I wrote exactly how I felt. So, I wrote down my name and everything. To the question "Who gave you the most stress?" I wrote down the name of the commanding officer. Later, I was summoned to the commanding officer’s room and had to hear all kinds of unpleasantries from him.

I think we helped the Kurds a bit. But I don’t know how it relates to our national interest. I believe if we really wanted to help them, we should have used the money for humanitarian purposes, not for the military.

You can see the pictures that the Defense Ministry shows to the public about us, for example, the ones in which we play with Iraqi children and participate in the rebuilding of the country. Actually, a very small number of us get to do that kind of work. The reason we went there was not to help them, but to return safely.

On the surface, we went there for the sake of peace, but actually it was because of the U.S.’s request. It is more than strange to think about the fact that for the past two years, a total of some 10,000 Korean soldiers have been to Iraq, but nobody died. That’s more than strange in a battle zone. But then, it also tells that you that we didn’t do much work there. We just stayed in the military compound.

Every time when there was a terror attack on American soldiers, we shuttered ourselves up. After some two weeks passed and everything had become quiet again, we went out to give candy to Iraqi kids.

There, we joked with each other that the reason we came there was to help the officers who came with us to Iraq get promoted. Some also said that we were there just to look after these officers.