|

|

After working in Yemen as a public servant, Jamal, his wife and their five children fled their homeland after civil war broke out. After sojourns in Greece and Malaysia, they arrived on Jeju Island on May 5. Salwa, the oldest daughter, looks out at the ocean during her interview with The Hankyoreh. (all photos by Kang Jae-hoon, staff photographer)

|

19-year-old Salwa recalls her journey from torn-warn Yemen to Jeju’s unfamiliar shores

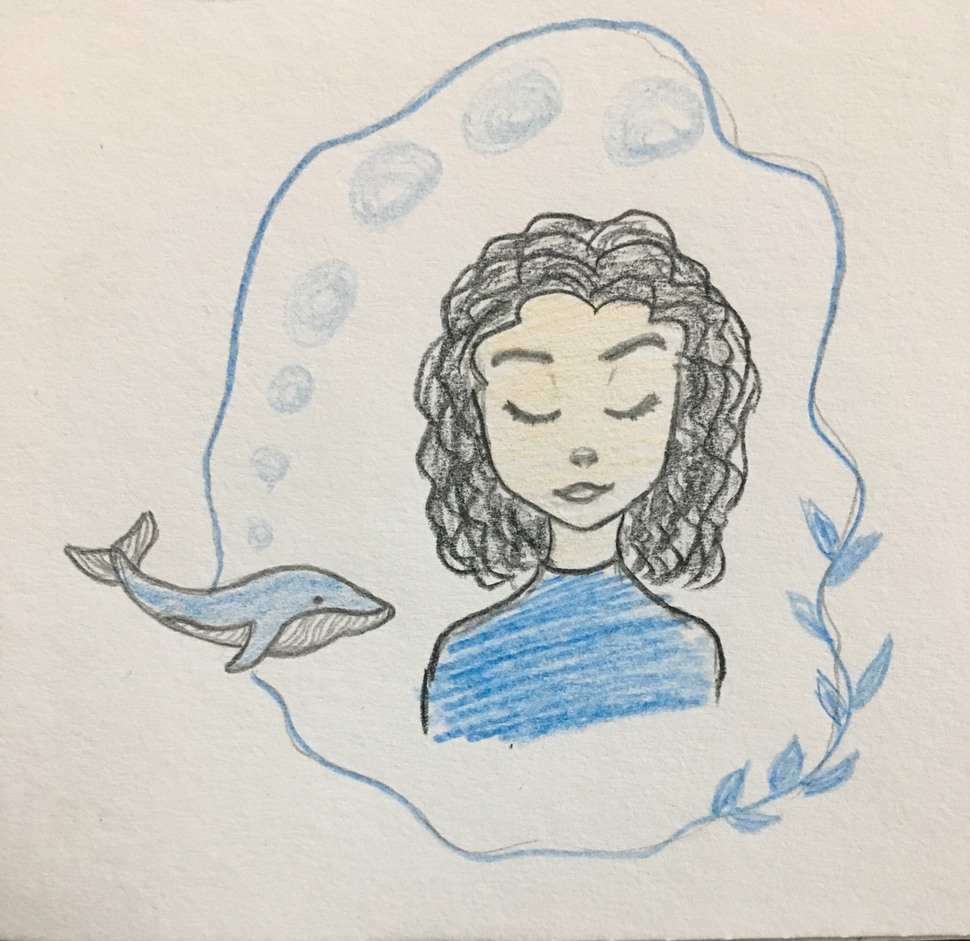

Where are the whales? The ancient Greek poet Arion was a wanderer who played the kithara (an ancestor of today’s guitar) and sang. His beautiful singing voice was like the sound of the heavens, and passersby stopped in their tracks when they heard his music, moved to tears as it washed over their souls. His reputation spread far and wide, and he began receiving invitations to perform around the world. He went to play in Sicily, where the people offered him jewels and expensive gifts, pleading with him to stay on the island forever. But he wanted to go home. Taking his leave as hundreds of Sicilians sadly saw him off, Arion boarded a boat – but the greedy sailors on board tried to kill him and steal his gold and jewels. Arion climbed on the prow and sang the last song of his life before plunging into the dark sea.

But he did not die. A pod of whales appeared, having heard his song from the ocean depths. They carried Arion on their backs and brought him back above the surface. After rescuing him, the whales swam around him as though to guard him on his way back home to Corinth. Arion lived on to continue performing beautiful music; each time, the story goes, the whales would come to the shore to listen. For millennia, the story of Arion has been a common theme for European painters. But is the story merely a legend? Images of Arion riding on the back of a whale were inscribed on silver coins in ancient Greece.

|

|

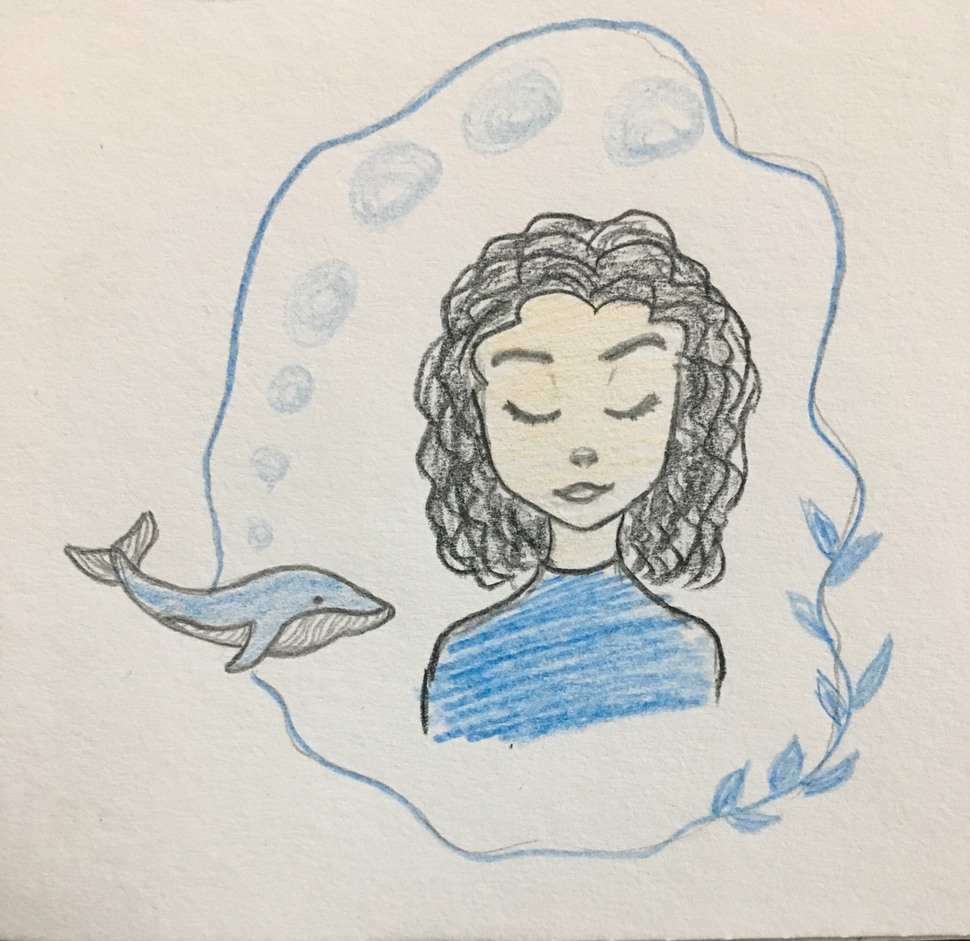

A friend of Salwa’s gave her a handheld mirror decorated with a picture of a whale.

|

No longer blessed with the sight of whales

Nineteen-year-old Salwa said she misses the whales. Back when her life was at its happiest and most peaceful, she lived by the sea. Salwa loved the blue of the ocean, and the sight of the whales swimming in it seemed to her like a miracle. She marveled at their massive size and smooth, streamlined forms.

She now lives on Jeju Island, but she has yet to encounter a whale there. She also has not had the luxury of visiting the beach. Salwa is a young refugee from Yemen. I met her and her family on Jeju Island on July 12. She had a shy smile and long eyelashes. I didn’t ask her about the complex political situation in Yemen or the plight of Yemeni asylum seekers. But I was curious how she had been doing and what she thought as an ordinary girl in her teens who had arrived in the strange land of South Korea. We ate and drank tea, spending a long time looking at the sea. We did not see any whales that day.

The weather was intensely hot. Salwa’s temporary residence was in a beachside village on the outskirts of Jeju City. I did not have an exact address for her until I arrived. When I called to tell her that I was at the village entrance, her father came out to greet me. As I stepped inside their house, his wife and Salwa’s five sisters came out and greeted me in turn. Salwa is the oldest of five girls. It was a silent greeting – not in Korean, Arabic or English – but a boisterous welcome in body language alone as the fourth sister (11) and youngest (eight) bounded up as if they had been waiting for our group.

|

|

Salwa during her interview with at her family’s temporary residence in a beachside village on the outskirts of Jeju City

|

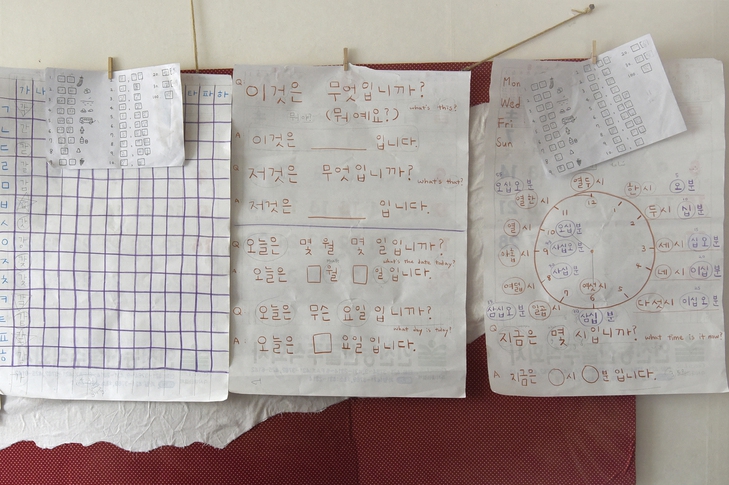

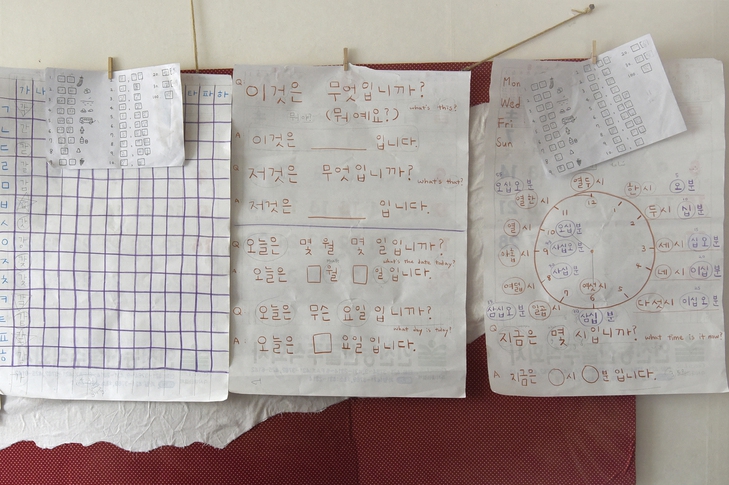

Father Jamal, 42, ushered us into a small room to the side of the entrance. Measuring just two or three pyeong (6.6–9.9 square meters), it had the only air conditioning in the house. The room quickly filled as the family of seven sat down inside. One of the walls was a Korean alphabet study guide, with Korean sentences showing questions and answers for telling time and the days of the week written on a large sheet of paper.

“Looks like you’re studying Korean,” I said.

“I have a Korean friend who comes over and helps me study Hangeul [the Korean alphabet],” Salwa replied.

Jamal, who had served as a government official with the agriculture department back in Yemen, interpreted using English.

“Do you all study together? Who’s the best at it?” I asked.

The youngest looked around and then pointed at Salwa, a shy smile on her face. Salwa, the second and third sisters (17 and 15, respectively), and their 42-year-old mother were dressed in long sleeves and pants with hijabs that covered their hair. The fourth and youngest sisters wore short sleeves and shorts.

|

|

Educational resources for learning Korean on Jamal’s wall.

|

“How long have you been wearing a hijab?” I asked.

“Since I was fourteen. I didn’t wear one when I was younger. I’ve been wearing one since adolescence.”

“Do you wear it inside the house, even on hot days like this?”

“I don’t wear it at home when it’s just family members, but I have to wear it if a man comes. Even if it’s my cousin, I still have to wear a hijab whenever a man comes over.”

“So it would have fine if it were just me, but you had to put one on because of him,” I said with a laugh, pointing at fellow reporter Kang Jae-hoon, who was there to take photographs. Seeing me mock-scowling at him, the young girls laughed, covering their mouths with their hands.

The room had a small wall air conditioner, but it did not seem to be working, because there was no breeze. A fan was brought in from the next room. It was the home of an ordinary South Korean family. A piano sat on one side of the room, and Korean picture books were neatly shelved in a low bookcase.

“I see there’s a piano here. Have you played it?”

“No. . . .”

|

|

Salwa said she believes in the “good of the world.”

|

Migrating from one temporary home to another

The family seemed to be cautious to avoid touching anything in the home, lest they trouble the owners allowing them full use of the rental unit. It was their second residence since arriving on Jeju Island. After coming in May, they met generous residents who allowed them to stay for a month or so on their farm before an acquaintance arranged for them to get permission to stay here for a month, they explained. Two weeks had already passed, and they had two weeks left to find a new place to stay.

“What is a typical day like for you?”

“I get up in the morning, eat, and clean up. . . . At about 2 pm, I go to the migrant center to study.”

After hearing that there was a four-hour daily study group from Mondays to Thursdays at the Jeju migrant center, Salwa’s father signed his children up a few days ago. In the classes, three of the sisters study with four classmates from Japan and China. These days, the classes are the time Salwa looks forward to as they offer an opportunity to study Korean, draw pictures, eat snacks, and talk. The center’s program is only for teenagers, so the fourth and youngest daughters are unable to attend. They explained that they were receiving “home schooling”; I didn’t have the heart to ask what materials they had to study with.

“What do your sisters do all day? Is there a TV?”

“We don’t have a TV. The WiFi comes and goes. When we do have WiFi, they watch YouTube videos on their phones.”

|

|

During the interview, Salwa’s father and older sister made us some khameer, or fried dough.

|

Salwa answered in a thin voice as she fiddled with her cell phone. For the family, cell phones are their only connection to the world. When they are lucky enough to have WiFi, the younger of the sisters watch their favorite children’s programs or look for news broadcasts from Yemen. It was through Yemeni news that Salwa learned about what an intensely debated issue the asylum seekers on Jeju Island had become in South Korean society. The parents had avoided sharing too many details, concerned their children might worry.

“Does the name ‘Salwa’ have any special meaning? What does it mean?” I asked.

“It means to make people forget their worries and be happy. My father gave me the name.”

“When are the happiest times for you, when you forget your worries?”

“When I go out to meet my Korean friends. I went to a place called an ‘oreum’ [a small defunct volcano on Jeju Island]. It was really beautiful.”

“Have you been to the beach here? If you go a little bit that way, the sea is there.”

“No. . . .”

“You have the Jeju sea right nearby. Why don’t you go? It’s only about a five-minute walk.”

She didn’t answer, offering only a smile. Salwa does not go out very much at all, except when a group of Christians helping the family come to give them rides. She does not walk around the neighborhood alone or go out to the beach with her younger sisters. Perhaps it is her gesture to avoid upsetting neighbors who are not so friendly, in a strange land where she does not understand the language or alphabet.

“So your name means to ‘take away worry.’ What is your biggest worry?”

“School. I have to graduate from high school. . . .”

Salwa has been unable to attend school for three years since graduating middle school. Spending her time alone while others are busy preparing for their future is a source of anxiety and concern. She often frets over what she will be able to do in the future at this rate. In a normal environment, she would have already graduated high school and entered a university – but no school would permit her to enter now.

|

|

Salwa wrote her name in Korean.

|

”Strangers wherever we go”

Salwa is capable of holding a simple conversation in English, but when she had to speak at length, she would ask her father to interpret or type a sentence into the Google translator on her cell phone and show me the English translation. After returning from our meeting on Jeju Island, I sent her a few additional questions by email in the hopes of having a longer conversation with her without her father interpreting. Each time, she would send me a sentence that had been written in Arabic and translated into English. The letters were adorable, with hearts and smiley emoticons interspersed among the sentences.

“Koreans know virtually nothing about Yemen. What is that country like?”

“It’s a lot different from Korea. It’s in the middle of a civil war right now, but I’ll go back someday, when the war is over and it becomes safe,” Salwa said.

“You’d really want to go back despite all the trouble it’s caused you?”

“That’s where my friends and family are. That’s where people speak my language, and it’s the place of my birth. Even if we spend a long time overseas, we’re strangers wherever we go. It never seems like my own country.”

|

|

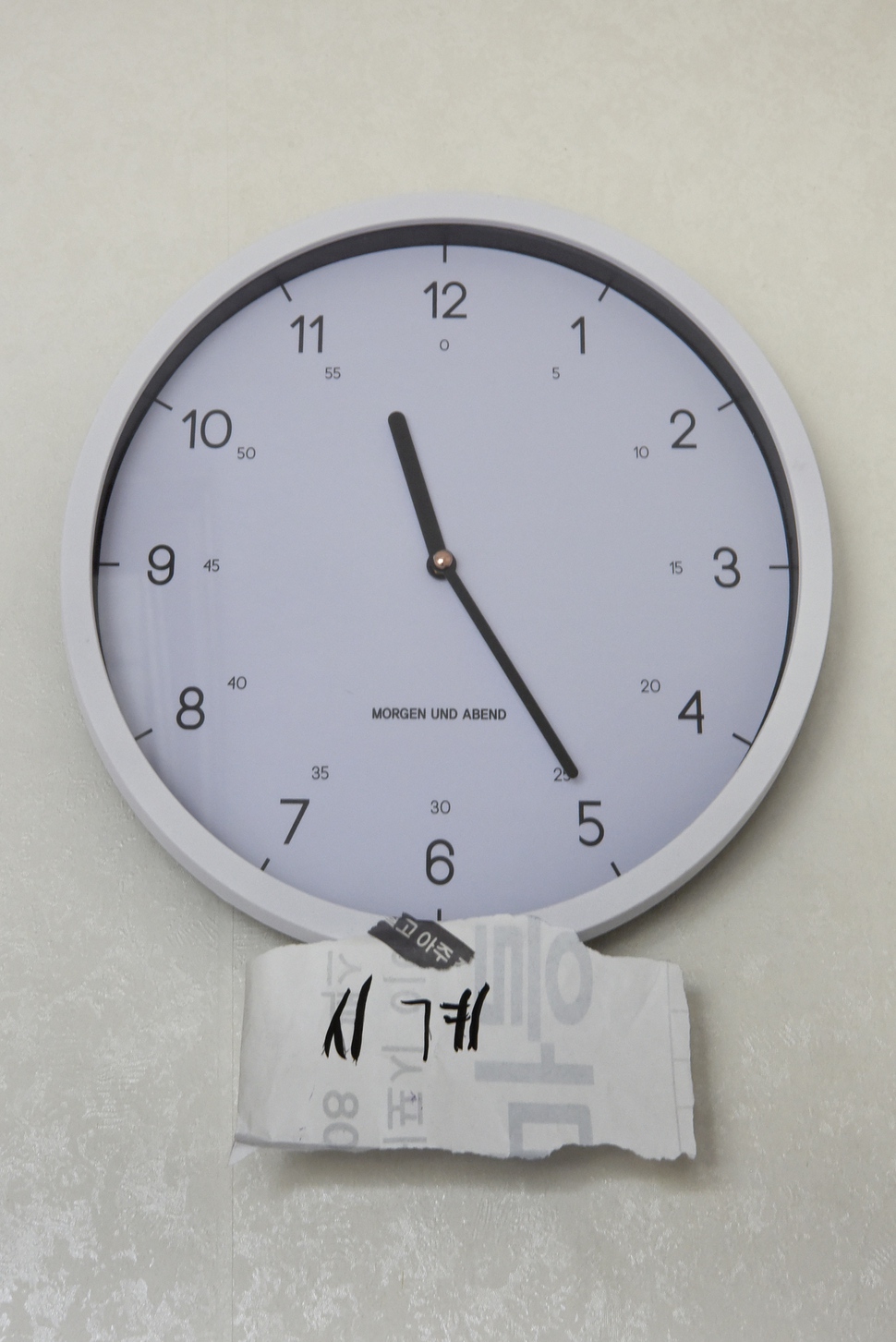

Salwa and her sister have labeled households objects with Korean notes to better learn the language.

|

A life interrupted by civil war

Salwa was born in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen, in 1999. Her father majored in trade at Sana’a University and got a job as a public servant. He married Salwa’s mother when she was 23 years old, and Salwa was their firstborn. In one of the handful of pictures the family brought with them from Yemen, Salwa is grinning from atop a horse draped in flowers at the age of five or six. When she was born, Yemen was enjoying a time of peace and stability without any major conflicts.

But when the country was overtaken by political strife in 2006, the family relocated to Greece. Their situation there was precarious and challenging, but Salwa was excited about going to elementary school and had a great time making new friends. She was nine years old at the time. Her father applied for refugee status at the UN office in Athens and had to renew his ID card every six months. He was given a work permit and did odd jobs at a curtain factory. As a former office worker, her father wasn’t used to manual labor, and his wages were hardly adequate to support his family.

Even so, Salwa remembers little of her family being poor. While the family was waiting for approval as refugees, her mother became pregnant with their youngest child. Her morning sickness made her long to go home. In 2010, the family finally gave up its refugee application and returned to Aden, a port city in southern Yemen where Salwa’s maternal grandparents lived. Before long, the civil war reached the south and forced the family to flee to the hill country in the north. Even so, the two years Salwa lived with her grandparents were the happiest years of her life.

“Who all was living with you?” I asked.

“There was my grandmother, grandfather, and four aunts. Two of them were married, while the other two aunts and an uncle lived with us. The saddest part was when my grandfather passed away. I didn’t have a chance to tell him how much I loved him, and he passed away before he could tell me how to deal with dark times in my life. My grandfather’s death turned my world upside down. It was as if my teacher, coach and steady role model had died,” Salwa said.

|

|

A picture drawn by Salwa of her mother

|

“But it was still the happiest time of your life?”

“My grandparents’ house was very close to my school, and it was close to the ocean as well. I had a clear view of my school from our fifth-floor balcony. I still remember the neighborhood like it was yesterday. There was the marketplace, the streets, the stores, and the fishmonger. Each alley is full of memories that are so special and beautiful to me. Even today, all my mom’s relatives live there. My aunts were 22 and 24 years old back then, and I was especially close to my youngest aunt.”

“Wherever you go in the world, the youngest aunt is always sweet,” I said with a laugh.

“You’re right. My aunt was like a second mom to me. I was so happy to have an aunt like that. I enjoyed all the time I spent with her. Sometimes, we would go down to the ocean and buy groceries together at 7 in the morning. In the evening, we would grill freshly caught fish we had rubbed with salt and spices. It’s already been five years since the last time I had that, but I still haven’t forgotten how it tastes. We went everywhere together: the parks, markets, restaurants, and stores. . .

“I just loved sitting close to her. We always played together and listened to music together. We would go up to the roof and eat noodles, and when it was hot, we would sometimes sleep up there, too. When the electricity went out, we used to just gaze up at the stars in the night sky. My uncle would bring us some warm milk. I really miss everything about those days.”

“You didn’t see any of the war for yourself?” I asked.

“When we came back from Greece, Aden was a fairly safe place. I was young and had little awareness of the war. When the fighting reached the south, we fled to a new area in the north, so I didn’t personally experience the war.”

“What’s the point of all the fighting?”

“They’re trying to win. Each faction is just trying to beat the other factions.”

“Who do you think will win?”

“There are no winners. One person kills another until eventually they all die.”

“If not for the war, what would your life be like?”

|

|

A self-portrait by Salwa

|

Imagining life without the war

“If I were still there, I would probably be going to university. I might have been able to prepare for an early graduation. Not being able to go to school means I’ve basically wasted three years.”

When the topic of school came up, Salwa’s expression darkened once more. When the civil war had heated up in 2011, Salwa’s father had gone to Malaysia alone and then had his family join him two years later.

“Didn’t you feel nervous during the two years your father was gone?” I asked.

“No, I’ve never doubted that my dad would be there with us.”

The family went to Malaysia, but they had no guarantees there. Malaysia was not a member of the UN Refugee Convention and had not passed any laws about refugees. Salwa’s family had permission to stay there, but her parents had no legal right to work, nor the children to go to school. Fortunately, the nearly 20,000 Yemeni refugees in Malaysia had created their own community, which enabled Salwa to go to school through her ninth grade. But after completing middle school, there were no high schools that would officially enroll someone with her status of sojourn.

[%%IMAGE11%%]

Decision to come to South Korea

The biggest reason Salwa’s father decided to take the family to South Korea was his desperation to find some way to educate his daughters. Unlike Malaysia, South Korea had joined the Refugee Convention a long time ago and even had its own refugee legislation. This past May, Salwa and his family boarded a plane bound for Jeju Island.

“Did you know what Jeju Island would be like?

“Yeah, of course,” Salwa said.

“Had you heard anything about South Korea before coming here?”

“My friends in Malaysia watched a lot of Korean dramas. We watched Who Are You? and had a good time watching a drama called Bring It On, Ghost, too.”

“What was your first impression of Korea when you got off the plane at Jeju Airport?”

“I thought it was a lot different from Malaysia. I got the impression that everything was much more organized, detailed, and rational. The moment I got off the plane, I felt relieved, because I thought we were safe now.”

“Do you think you’ll be able to stay in Korea for a long time?”

“Yeah,” Salwa said without hesitation.

I was taken aback by the complete certainty in Salwa’s voice. Does she really not know what Koreans are saying about the Yemeni refugees? Is she really unaware that more than 700,000 people signed a petition against the Yemenis and that protests are being held against them in Seoul and on Jeju Island? While I hesitated, unsure of where to begin, Salwa continued speaking.

“Koreans are really nice,” she said, smiling brightly. “There are some people who misunderstand Yemeni refugees and Muslims, though.”

“Take a look at this,” she said, as she held out a photo of a handheld mirror. “A Korean friend gave this to me as a present. I hadn’t even said I like whales and the color blue, but they gave me this present as if they knew all about me. I really love it when something makes you happy when you least expect it.”

When my eyes met those of Salwa’s father, who was sitting beside me, he grimaced and lowered his head. It was obvious he hadn’t given his daughters all the details about the outside world because he didn’t want to make them upset. For some time now, Salwa’s younger daughters had been peeking into the room, assuming it would be time for lunch any minute. While they were listening, I couldn’t say anything more about the current state of affairs in South Korea. I made up my mind to continue the conversation after lunch.

[%%IMAGE12%%]

The sweetest, saddest dining table in the world

The family seemed to have gone to extra trouble for their guest. They served chunks of steamed chicken and a type of Yemeni bread made by kneading dough and deep-frying it in oil. When I asked what the bread was called, the youngest daughter, who was eight years old, told me it’s called khameer and then giggled at my poor pronunciation when I tried repeating the word. The five children squeezed around the dining table in that tiny room to eat their meal. It was at once the sweetest, and saddest, dining table in the world.

“After you’re finished eating, how about we go down to the sea together?” I asked, feeling quite uncomfortable about the whole meal. Perhaps I was just trying to get out of that situation. After lunch, Salwa and her father got in my car, leaving the rest of the family behind, and we headed off. The beach nearby was packed with tourists, so we turned around and found a quiet café by the sea. We sat down at a table outside where we could hear the waves.

“How are you covering your current living expenses?” I asked Salwa’s father. It was the question I’d been unable to ask him back at the house.

“I ran out of the money I’d saved up, We were getting by on remittances from Yemen, but now that has nearly run dry, too. Right now, we’re getting by thanks to the help of several gracious individuals, but I’m not sure where we’ll go in a couple of weeks. Since I have five daughters, it’s not like I can go to just any old place,” he said with a sigh.

“Are you looking for a job?”

[%%IMAGE13%%]

“Most of us are working on the fishing boats, while a few are on the farms. Generally, we Yemenis were farmers in the hill country to the north, and we’re not used to boats. I was willing to do any kind of job and had arranged to work on a boat, too, but then they wouldn’t let me because the boat ranges beyond the Jeju coastline. Refugees aren’t supposed to leave Jeju Island, they told me.”

“There are a lot of people who bear you good will, but no small number feel hostility for the Yemeni refugees,” I pointed out.

“I understand that. We’ve run into that kind of attitude everywhere we’ve been. Some people do feel that way about strangers. Even inside Yemen, people treated us like foreigners when we moved from the south to the north, and then back from the north to the south.”

During this conversation, Salwa’s big eyes bulged.

“Is this the first time you’ve heard about this?” I asked her.

“Yeah, my parents didn’t tell me about this,” she said, haltingly.

“Ten years from now, where would you like to be and what do you want to be doing?”

“My dream used to be majoring in science at college and starting a business that makes natural cosmetics. But now—” Salwa paused before continuing. “The most important thing is to settle down somewhere safe. I’d like to quickly wrap up my studies and help my father pay the rent.”

The Jeju sea was dazzlingly blue, and whenever there was a lull in the conversation, we would listen to the sound of the breakers.

A few days later, Salwa wrote me the following email.

[%%IMAGE14%%]

A message for Koreans

“After we met, I thought about the difficulties that we refugees are facing. I understand that Koreans are worried and afraid about strange foreigners showing up here. But refugees are people who have fled their homes because they can’t live there during the war. If not for that, who would want to leave their homes, the place where they were born and raised? The worst thing for any parent is raising their children in a warzone, unsure of whether the children will still be alive tomorrow. If you haven’t been through that yourself, you can’t know what it’s like. But I believe there are more good people in this world. Good people who find meaning in helping others and doing good things. That’s why life is still beautiful. I still haven’t given my little sisters all the details about the situation. I don’t want to make them worried or sad. Sometimes I feel a little despondent, too, but I will stand up again. I will believe in myself and in the good of the world and that every day will bring new opportunities.”

I loaded a photo of Salwa that was saved on my phone. The 19-year-old girl was standing there, blankly, in front of the blue sea off Jeju Island. When will she get to see a whale? All we could see was the open sea and the white waves, but perhaps a whale had swum up close and was watching us from underwater.

By Lee Jin-soon, founder of WAGL (we all govern lab)

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]