|

|

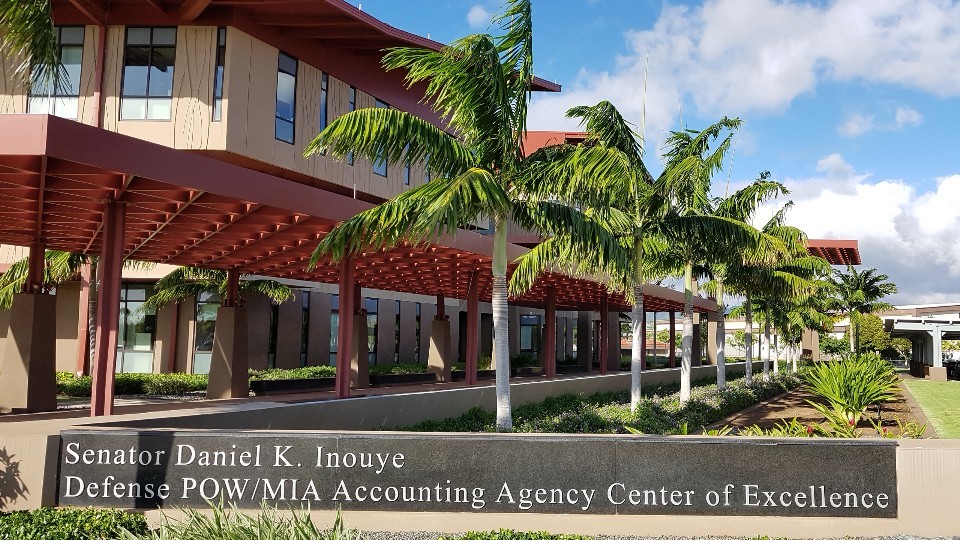

Dr. Jennie Jin (Jin Ju-hyeon), director of the Korean War Project at the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), at the US Department of Defense, explains the process of recovering the remains of Koreans who were forced into serving Japanese troops during the Battle of Tarawa in WWII at the Indo-Pacific Command base in Hawaii on Oct. 23. (photos by Lee Je-hun)

|

Dr. Jennie Jin explains the difficulty of recovering remains of Koreans conscripted into labor

“Do you know about Tarawa?”

When the speaker paused her patient description of the identification of human remains to ask this abrupt question, people in the audience looked around blankly.

Smiling broadly, the speaker continued: “Probably not. I didn’t know about it either until the first time I went there. When Koreans come by, I always bring them here to talk about Tarawa. It’s just such a shame.”

The speaker was Dr. Jennie Jin (Korean name Jin Ju-hyeon), who is in charge of the Korean War Project at the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), at the US Department of Defense. The mission of this project is to recover and identify the remains of people who were killed or went missing during the Korean War. Recently, Jin has focused on identifying the remains of the American soldiers in the 55 boxes that the North Koreans handed over to the Americans on July 27.

Jin also took part in the repatriation ceremony for the remains that was held at Kalma Airport in Wonsan, North Korea, where she assessed the content of the boxes to ensure they did not contain animal bones. Just as before, no animal bones were found in the boxes that the North Koreans said contained the remains of American soldiers.

Around 1,200 Korean forced laborers sacrificed in Battle of Tarawa

|

|

Dr. Jin explains the process of confirming the identity of Koreans forced into labor under the Japanese imperial army using their remains.

|

So why did Jin ask the South Koreans in the South Korea-US Security Forum delegation who visited DPAA, at the Indo-Pacific Command base in Hawaii on Oct. 23, whether they knew about Tarawa?

The small island of Tarawa in the South Pacific, which is gradually being submerged by global warming, is the capital of the Republic of Kiribati (population of 100,000). Tarawa is composed of several atolls, the largest being Betio, which is 3km long and 800m wide.

Between Nov. 20 and 23 of 1943, Betio was the site of a desperate battle between American troops trying to land on the atoll and Japanese forces determined to stop them. The battle was a 72-hour bloodbath in which 1,696 Americans, including 900 marines, and 4,690 Japanese lost their lives. The name that war historians have given this first amphibious landing that affected the course of the War in the Pacific is the Battle of Tarawa.

Another part of Jin’s job is to recover and identify the remains of American troops buried on Tarawa and return them to their families. “The American government has been working hard and getting results. Japanese NGOs are also traveling around islands in the Pacific Islands and recovering remains.”

But it turns out that the US and Japan aren’t the only countries concerned. The American soldiers who overcame the Japanese resistance and landed on the island took 145 prisoners, 128 of whom were Koreans conscripted into labor. Records show that 1,400 Korean forced laborers had been brought to the island to fortify it. That means that more than 1,200 other workers were killed on the island – not in the suicidal charge of Japanese soldiers screaming “Bonzai!” but as human shields whimpering for their mothers.

Jin continued speaking: “When the Japanese find remains, they cremate them on the spot. Their explanation is that, because of regulations and sanitation, the remains can’t be taken back to Japan. The problem is the extremely high likelihood that the remains of Korean workers who were brought there by force are mixed in with the remains that they’ve cremated. South Korea has never recovered any remains there. I’m told that South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of the Interior and Safety have told the Japanese not to cremate any remains they find on site.”

Jin’s journey from Korea to the US as an anthropologist

Jin is currently an American citizen. Born in South Korea, she studied archaeology in the Department of Archaeology and Art History at Seoul National University. After being selected as a scholarship student for the Korea Foundation for Advanced Studies, Jin completed a master’s degree in anthropology at Stanford University and a doctorate in the same subject at Pennsylvania State University. In 2010, she was hired by the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC, today called the DPAA), and since the following year she has been in charge of identifying the remains of American soldiers from the Korean War that have been returned by North Korea.

|

|

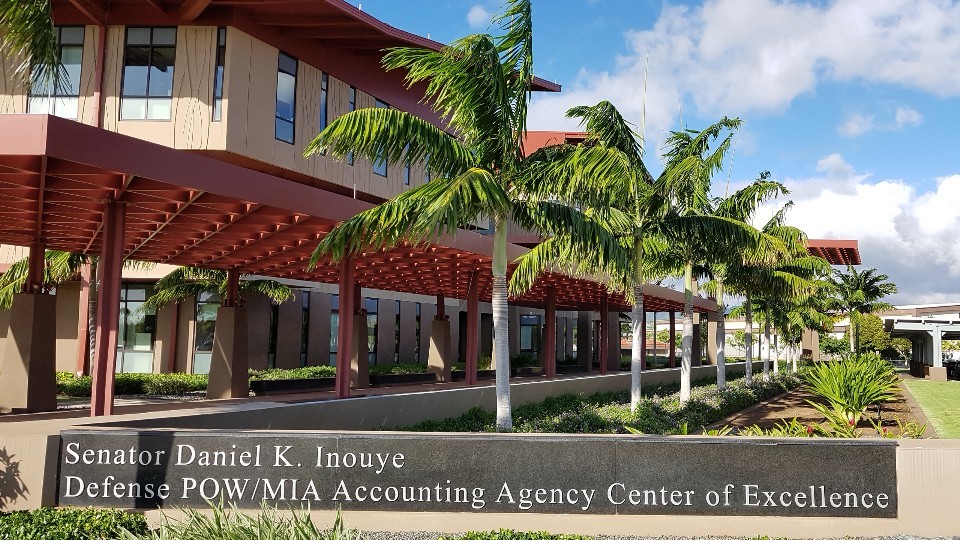

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), in Hawaii

|

Jin is a forensic anthropologist. Forensic anthropology, as she explains it, “is the field in which you use anthropological, biological and anatomical knowledge to determine a deceased individual’s age, height, gender and the time and cause of death.” A number of books written by Jin, including “The Story the Bones Told,” have been published in South Korea.

Jin frequently works alongside the South Korean Defense Ministry’s Agency for Killed in Action (KIA) Recovery and Identification. On Armed Forces Day, on Oct. 1, Jin was once again working on an identification project – in this case, 64 sets of Korean War remains that had previously been excavated by the US and North Korea and were recently returned after being determined to belong to South Korean troops. “The biggest difference between how identification is handled in the US and South Korea is the question or whether or not there’s a record of war dead,” she said. The US not only has records of war dead but also detailed information about troop strength, but in most cases South Korea does not have any records at all.

Such fundamental differences also have a major effect on the weight given to personal effects in identifying remains. “For us, personal effects don’t play a big role in identification. We don’t regard identification as being confirmed until we’ve gotten some kind of biological evidence through a DNA or isotope analysis or chest X-rays. In South Korea, in contrast, personal effects play a major role. Perhaps that’s why South Korean experts are so good at figuring out whether soldiers are South Korean, North Korean or Chinese simply by looking at uniforms so old they’re falling apart. It’s remarkable, really.” Jin said.

After the interview was over and I was turning to go, Jin called after me to make one final request: “When you get back to South Korea, please tell a lot of people about Tawara. I just feel so bad for the people who were forced to get there only to lose their lives.”

By Lee Je-hun, senior staff writer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]