|

|

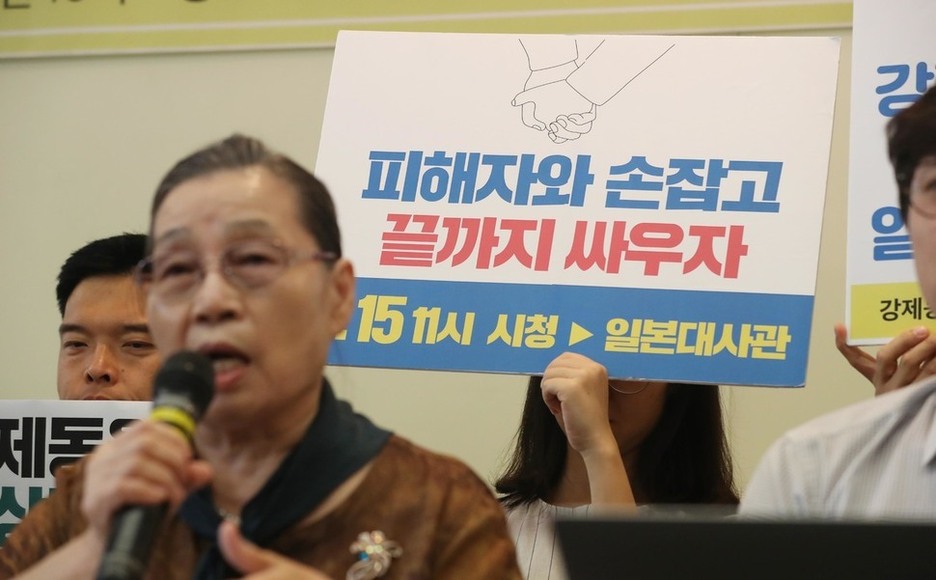

On Aug. 8, Lee Hui-ja, co-president of the Council for Securing Compensation for Pacific War Victims, talks during a press conference calling for the resolution of issues related to forced labor under imperial Japan at the Franciscan Education Center in Seoul. (Park Jong-shik, staff photographer)

|

Lee Hui-ja’s father was forced to serve in the Japanese imperial military during WWII

In February 1944, Lee Hui-ja (today 76 years old) was living with his family on Gangwha Island when his father was press-ganged by the Japanese military. Lee had just turned one year old. Before departing, Lee’s father promised the family that he’d come back soon, but they never heard from him again, even after Korea’s liberation from Japan’s colonial occupation. After joining the Association for the Pacific War Victims, Lee spent years searching for traces of his father and finally learned of his final resting place in 1997 — Japan’s controversial Yasukuni Shrine. Lee’s spirit tablet had been enshrined there, after he was killed in battle during the War in the Pacific. Lee was infuriated to learn that his father, after being forced to join the Japanese military against his will, was receiving religious honors as if he’d laid down his life for the Japanese emperor. Now, 23 later, Lee is co-president of the Council for Securing Compensation for Pacific War Victims, where he is working to restore the reputations of drafted Koreans who were laid to rest at Yasukuni. At 2 pm on Aug. 15, the documentary “Annyeong, Sayonara” was screened at the Museum of Japanese Colonial History in Korea, in Seoul’s Yongsan District. The documentary is about the lawsuit that Lee filed to remove his father’s spirit tablet from Yasukuni Shrine. Some 20 people had come to the museum to attend the screening, which fell on Liberation Day. As the star of the documentary, Lee himself was present, along with Hideki Yano, 69, a Japanese activist and the secretary-general of a group called Joint Action to Resolve the Issue of Compulsory Mobilization and to Settle Japan and Korea’s Historical Disputes. Lee and Yano were there to talk with the visitors. Along with Lee’s lawsuit, “Annyeong, Sayonara” also presents the stories of other victims of compulsory mobilization. In 2001, 2003, and 2013, these individuals filed lawsuits at Japanese courts against the Japanese government and Yasukuni Shrine, calling for the end of the practice of unauthorized enshrinement. Out of concern that their lawsuit might be mistaken for a cash grab, they asked for only 1 yen in damages. But time and time again, the courts either ruled against them or threw out their lawsuits altogether. In their decisions, the Japanese courts argued that the government had no authority to meddle in a “religious facility,” namely Yasukuni.

|

|

Civic demonstrators rally in opposition to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his policies in Seoul on Aug. 15, Korea’s Liberation Day. (Baek So-ah, staff photographer)

|

|

|

Civic demonstrators hold a candlelight vigil in opposition to the policies of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in Seoul’s Gwanghwamun Square on Aug. 15, Korea’s Liberation Day. (Baek So-ah, staff photographer)

|