|

|

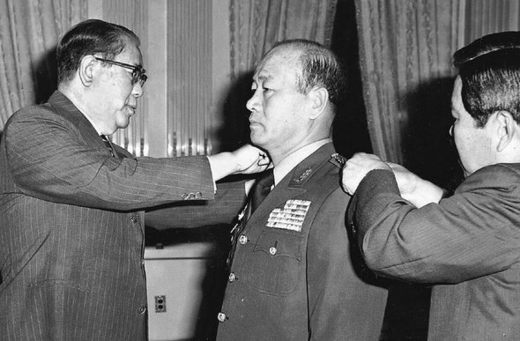

In 1980, then president Choi Kyu-hah (left) and general Chun Doo-hwan.

|

Korea lacks a ’culture of confession’ about its past

Many are upset because former president Choi Kyu-hah, who passed away on October 22, never revealed any details regarding the military coup that ousted him and placed Chun Doo-hwan in power. Choi may have been able to clear up some questions about that dark time in 1979 and 1980 in South Korean history, when the hope of democracy was quickly crushed. Indeed, he was asked about the period repeatedly; he refused to divulge anything, and now he has carried his secrets to the grave. There are a number of former high-ranking figures in South Korean history who have refused to divulge truths about history, leading some historians to charge that Korean society lacks a "culture of confession." Former power elites of South Korea’s military regimes, in particular, continue to keep silent regarding incidents of political manipulation and human rights abuses, the lines of which often blur in South Korea’s modern history. Lee Hu-rak, director under the Park Chung-hee regime of the Korea Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA) - the predecessor of the National Intelligence Service (NIS) - has refused to reveal any truths about the kidnapping of former president Kim Dae-jung in 1973 or the mysterious death of Professor Choi Jong-gil of Seoul National University. Choi was found dead while under investigation on charges of espionage in the early 1970s.Chang Se-dong, who served as director of the Agency for National Security Planning under former president Chun Doo-hwan, even offered this response at a National Assembly hearing on his role in a series of abuses committed under the regime: "If I open my mouth, the nation will be in danger." In connection with the December 12, 1979 military coup that set the stage for Chun Doo-hwan taking over the presidency, and the May 18, 1980 Gwangju Massacre, former presidents Chun Doo-hwan and Roh Tae-woo have neither confessed nor repented for their roles in the military’s killing of hundreds of student protestors. A few former heads of state have published memoirs, but they have been assessed by historians to be less than forthright records of the past. Professor Hong Seuk-ryul of Sungshin Women’s University said that some memoirs, including those of former prime minister Chang Myun and former president Yoon Bo-sun, fall short of giving details, in some cases merely justifying the former officials’ actions and asserting that they have done nothing requiring censure. Others that were not high-ranking officials but still may have important information to tell have kept silent, as well. Kim Hyon-hee confessed to the national intelligence agency that she had helped to plant a bomb on Korean Air Lines flight 858 on November 29, 1987, killing all 115 aboard. She said that she was a North Korean operative, and that the order to blow up the plane came from Kim Jong-il himself. But she received a special pardon from the government, and the families of victims have cast doubt on some of the government’s explanations through the entire duration of the investigation, and have demaned more questioning of Kim Hyon-hee. But she has remained in hiding; even a large-scale reinvestigation of unresolved events launched by the government in 2004 failed to contact her. One government investigator on the team investigating unresolved incidents said, "We have held questioning sessions with 100 alleged wrongdoers, but only 1 in 10 confessed his acts." There have been a few notable exceptions. Choi Rin in 1919 was one of the 33 signatories of the Declaration of Independence from Japanese rule; however, he later went on to side with the Japanese colonial government. Lee Hang-nyeong also collaborated with the Japanese government, later becoming president of Seoul’s Hongik University. Both have since confessed to their activities during the colonial period. In another case, in an interview with Hankyoreh 21 a few years back, Kim Gi-tae, a retired military officer, testified that South Korean soldiers massacred civilians during the Vietnam War. Professor Han Hong-gu of Sungkonghoe University said that existing conflicts of interest among the wrongdoers in South Korean history tend to keep individuals from speaking out. The root of this phenomenon, Professor Han said, is the insufficient clearing up of, punishment of, and amendment for wrongdoings in South Korea’s modern history. Moreover, persons who hold secrets about the nation’s past are growing thinner in number. Ahn Doo-hee, who assassinated Kim Koo, one of Korea’s most renowned independence fighters, kept mum about the act; he died in 1996. Kim Hyung-wook has been missing since the mid-1970s. He was director of the KCIA during the East Berlin incident in 1967, in which a group of South Koreans were brought to South Korea on charges of espionage. Kim has not left behind any record regarding his or his agency’s role in the incident; what has been called an act meant to garner support in South Korean society for Park Chung Hee’s security-first regime will likely remain part of the silence of South Korean history.