After 9 years of no use, capital punishment still on books

|

Posted on : Dec.28,2006 16:34 KST

Modified on : Dec.29,2006 13:18 KST

|

|

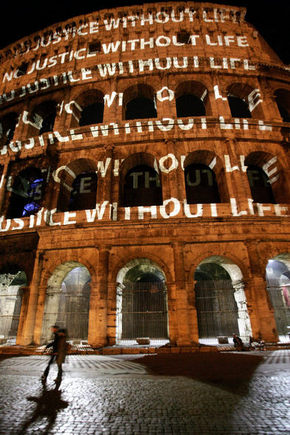

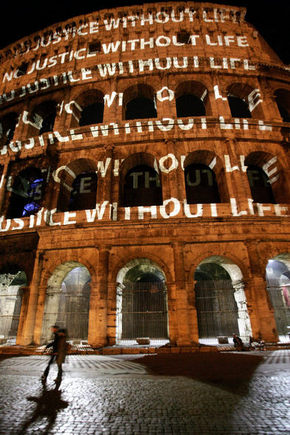

Coliseum on November 30, with a claim against capital punishment on the wall. (AFP Yonhap)

|

Rights group say issue is 'unimportant' to lawmakers

Twenty-three people were executed in South Korea on December 30, 1997. No one has been executed in the nine years since. Yet President Kim Dae-jung, himself once sentenced to hang before eventually winning the Nobel Peace Prize, and President Roh Moo-hyun, who calls himself progressive and reformist, were both unable to abolish capital punishment in Korea. The novel

("Our Happy Time") by Gong Ji-yeong, a story about men on death row, and the recent election of Ban Ki-moon as United Nations Secretary-General, have reignited the discussion about abolishing the death penalty, but another year comes to a close without any real progress on the issue.

In October, Amnesty International organized an "anti capital punishment day" in Seoul and started something called the Anti Death Penalty Asia Network. Amnesty called on Korea, as a member of the UN Human Rights Council and the home country of the UN Secretary-General, to be the first in the region to abolish it. "Korea should be the first country in Northeast Asia to do away with the death penalty," it said in a statement. In April of last year, the National Human Rights Commission formally recommended capital punishment be done away with, and religious groups have consistently called for the same.

The National Assembly holds the key to the country's future on the issue, and yet it is deliberately ignoring the issue. No less than 175 members of all the parties, led by Uri Party's Yoo Ihn-tae, who was sentenced to death in 1974 for political "crimes", submitted a bill calling for an end to capital punishment long ago, but it remains before the Legislative and Judiciary Committee. In February, it looked like things were picking up with public hearings and the like, but in the second half of the year the committee had a major change of membership and now everything is back to square one. Members that had been ready to move against capital punishment are now on other committees, and now nine of its 16 members are legislators who never signed the original bill.

Kim Hyeong-tae, a lawyer with a national Catholic committee on human rights says it "had little effect trying to persuade members of the Legislative and Judiciary Committee." He says he thinks they aren't doing anything about the issue because "if they oppose abolishment they'll be yelled at, and passing it won't be much benefit."

Kim Hui-jin of Amnesty Korea says that if you meet them privately, National Assembly members will say they support getting rid of the death penalty, but that it isn't enough of a priority to even be discussed. Bills to abolish it were submitted during the Fifteenth National Assembly and again during the Sixteenth, but were automatically discarded along with other unlegislated bills every time each of those assemblies came to a close.

The situation is not without hope. Amnesty International classifies countries that have capital punishment but don't execute anyone for ten years or more as countries that essentially do not have the law on the books. The last time Korea executed anyone was December 30, 1997, so if the next year is an "uneventful" one, Korea gets to be a nation that sits with those that don't "have" capital punishment anymore. It is not very likely the government of Roh Moo-hyun is going to order any executions to be carried out.

Kim Hyeong-tae with the Catholic human rights committee said, "Once Korea hasn't executed anyone for a decade, it will be hard for any future president to order an execution." He says it will be "politically very meaningful" if Korea is classified as a country without capital punishment a year from now. Kim Hui-jin, however, notes that Amnesty International has been unsuccessful at getting Korea to abolish the death penalty officially, despite having made Korea a key focus point for its campaign. "Getting it off the law books is essential if we are going to prevent the situation from depending on the political makeup of future governments," she says.

According to Amnesty, as of last year, 68 countries had the death penalty, and 122 have abolished it. Of the 68 countries that have it, 64 have prisoners on death row.

Please direct questions or comments to [englishhani@hani.co.kr]

© 2012 The Hankyoreh Media Company. All rights reserved.

No part of this material may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, mimeographical, in recorded form or

otherwise for commercial use, without the permission of the Hankyoreh Media Company.