Posted on : Nov.29,2017 16:36 KST

More than 2,000 people have drafted letters of intent rejecting life-sustaining treatment

During the first month of the trial period of a law allowing patients to decide whether to receive life-sustaining treatment, seven terminal patients have died after legally ending life-sustaining treatment or choosing not to receive it altogether. Over the past month, more than 2,000 people have drafted letters of intent declaring they do not wish to receive life-sustaining treatment when they become terminal patients, leading some to conclude that this will be a sea change in end-of-life culture in South Korea.

The Act for Hospice and Palliative Care and Decision-Making about Life-Sustaining Treatment by Patients at the End of Their Life (also called the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decision-Making Act), which was enacted by the National Assembly at the beginning of this year, will be taking effect in Feb. 2018. According to an interim report about the trial implementation of the law that was released by the Ministry of Health and Welfare on Nov. 28, there were a total of seven cases in which a decision to end life-sustaining treatment or to reject it altogether resulted in death between Oct. 23 and Nov. 24.

|

|

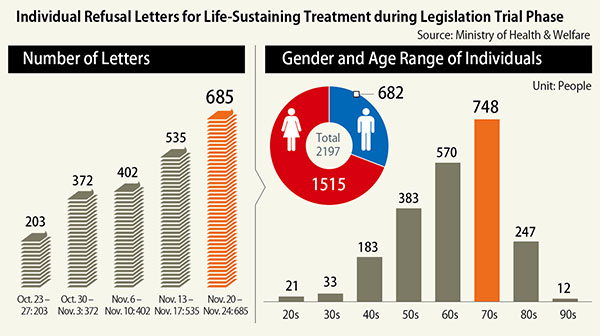

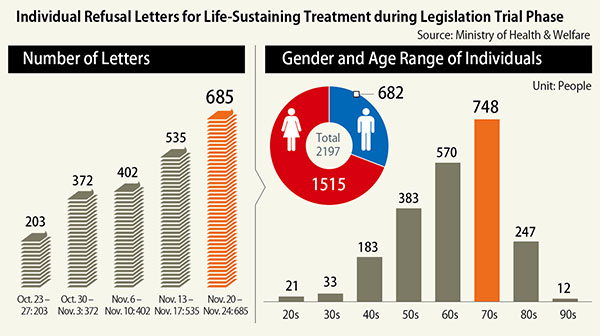

Individual Refusal Letters for Life-Sustaining Treatment during Legislation Trial Phase

|

Among these cases, there were two in which life-sustaining treatment was ended after the patient submitted a life-sustaining treatment plan, and there were four in which the patient had not written a plan but life-sustaining treatment was ended after at least two of the patient’s family members testified that the patient had not wanted such treatment. In the final case, the patient had not drafted a plan and it was impossible to know what they had thought about life-sustaining treatment, but such treatment was withheld with the agreement of all the patient’s family members.

During this period, there were 11 cases in which terminal patients drafted life-sustaining treatment plans following a consultation with a doctor. Ten of these were terminal cancer patients, and one had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. These plans are drafted after adequate consultations between the terminal patient, their family and a doctor, but since this is still the initial phase of the law’s trial period, not many plans have been drafted. This is presumed to be why there have been more cases of life-sustaining treatment being suspended on the wishes of the patient’s family than according to one of these plans.

Over the past month, a total of 2,197 preliminary letters of intent about life-sustaining treatment have been written, which is believed to reflect social interest in end-of-life planning. The age group most represented in these letters was people in their seventies, followed by people in their sixties and fifties, with over 200 letters written by people between their twenties and forties. The number of letters being written has been rapidly increasing each week, with over 200 written in the first week of the trial period and more than 680 last week (between Nov. 20 and 24). When the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decision-Making Act goes into full effect, the number of letters of intent being written is expected to greatly increase.

The Ministry of Health and Welfare is planning to address issues that have been raised during or prior to the trial period before the act takes full effect in Feb. 2018. To start with, the Ministry intends to make it possible for medical procedures to be added to those that are regarded as life-sustaining treatment (such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation and artificial respiration) by presidential decree and to allow not only terminal and dying patients but also those with just a few months left to live to write life-sustaining treatment plans. Another proposal is to enable the doctor attending someone who is receiving hospice care at a hospice center after being diagnosed as a terminal patient to determine that that patient is in the final stage of their life.

But there are still concerns in the medical community that the full implementation of the law will cause a great deal of confusion. “During the trial period, research at hospitals participating in the trial has been focusing on cases in which letters of intent or plans have been written. But in reality, all patients at emergency rooms, intensive care units and regular hospital rooms without this kind of plan will be eligible for life-sustaining treatment decision-making. We need to set up simulations about a variety of situations that could start to appear in hospitals next February and to determine how to deal with them,” said Yun Yeong-ho, a professor at the Seoul National University medical school.

By Kim Yang-joong, medical correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]