|

|

A screenshot from MBC’s “I Live Alone” program.

|

Single-person household policies customized for different generations and groups urgently needed

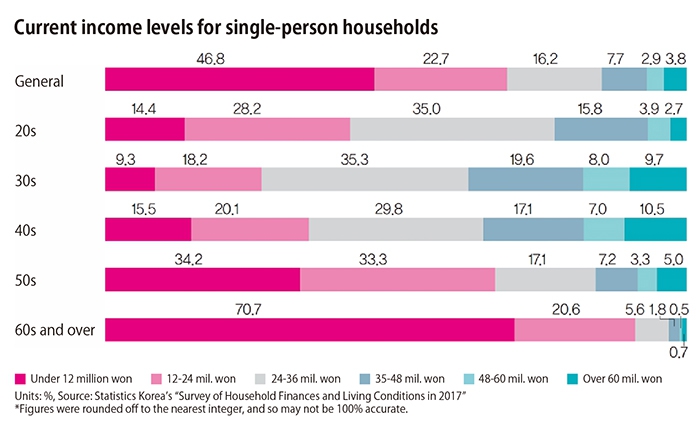

The sweet sound of jazz fills the air. The celebrity wakes up in a dark room, but the screen brightens when he/she pulls back the curtains. The window offers a fine view of downtown Seoul. The celebrity feeds his/her pet, which is already up and moving around the house. A flashy imported car awaits in the underground parking garage. Long after the morning rush hour has passed, the spotlighted celebrity cruises through the empty streets of downtown, lost in thought. This is a frequent sequence shown on “I Live Alone,” a variety show that has been broadcast on MBC since 2013. The producers of the show have described their goal as “building a social consensus since single-person households are the current trend.” But what viewers see on “I Live Alone” is a far cry from the reality of the five million people who live alone in South Korea today. According to Statistics Korea’s 2015 Family Finance and Welfare Survey, 50.6% of single-person households have less than 12 million won (US$10,621) in yearly income. The “Poverty Statistics Yearbook” published by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) reported a relative poverty rate of 45.7% for single-person households in 2016, based on their disposable income. That’s much higher than the relative poverty rate of 13.8% for households of multiple people. The relative poverty rate refers to the share of households whose income is no more than half of the median income (that is, the income of the middle household, if all households were lined up by income). The higher the relative poverty rate, the more severe the poverty of the affected group. The gap between “I Live Alone” and average single-person households The majority of people in single-person households aren’t “glamorous singles,” but “economically vulnerable.” The daily lives of celebrities seen on “I Live Alone” fail to reflect the actual conditions of single-person households today, which is why the show has also failed to “build a social consensus.” Single-person households are poorer than multi-person households where families live together. When the National Assembly Budget Office estimated the household income per family member in 2016, it found that the equivalized income for single-person households was 1.7 million won (US$1,500), which was much less than the equivalized income for multi-family households of 2.5 million won (US$2,213). Equivalized income is a figure that converts a household’s income to the income of household members in order to compare the income of households of different sizes. The equivalized income of single-person households at least 70 years old was 950,000 won (US$840), not even reaching the 1 million won (US$885) mark. It’s only among single-person households in their 30s (2.66 million won [US$2,354]) where income exceeds that of multi-family households (1.95 million won [US$1,725]). The lifestyle of the “glamorous singles” depicted in “I Live Alone” corresponds to a few of the highest earning even among those in their 30s. The number of single-person households continues to increase and is expected to reach 7.6 million by 2035, at which point it will represent 34.3% of all households. Experts and academics agree that aid programs should be developed that are tailored to the evolving and diverging characteristics of single-person households (age, residence, marital status, gender and so on). The bracket that demands the most attention from the community and support from the government is elderly single-person households, composed of individuals in their 60s and above. As the average lifespan has increased, one out of three single-person households fall in this age group. Amid the weakening of traditional family values, including the norm that people should provide for their aging parents, many single-person households in their sixties and above were left alone when their spouse passed away. Statistics show that 49.2% of single-person households in their 60s and 86.9% in their 70s are the result of spousal bereavement. 80% of single-person households in 70s and above are elderly women The average lifespan of women (86.17 years in 2015) is longer than that of men (78.98 years), resulting in a large number of elderly women in single-person households. As of 2015, 80.4% of single-person households in their 70s or above consisted of women. Female elderly single-person households are vulnerable in each of those three respects (female, elderly and single-person household), and they also face the triple threat of social isolation, unstable housing and poverty, and health problems such as dementia and chronic disease. Elderly women who have spent their lives under the traditional social structure and labor market are likely to depend on “transferred income” in the form of pension or inheritance from their deceased spouses rather than their own work income. In her paper “Current Conditions of Elderly Women in Single-Person Households and Policy Remedies,” Song Yeong-sin, president of the Senior Hope Community, called for government aid based on the three pillars of economy, healthy and society. Song elaborates her argument as follows: “There also needs to be a revision of the national pension system, which was originally devised on the assumption that the man is the breadwinner and the woman is a dependent. More women have to be admitted into the labor market to increase the national pension service’s coverage of elderly women in single-person households. Aid programs for elderly jobs also need to be made more accessible for elderly women in single-person households. It’s easy for such women to become marginalized, so support should be given to various forms of collective living arrangements, as advanced welfare states do, so that these women can form and support social networks.” Even single-person households in their 30s – the only age cohort in which single-person households have higher equivalized income than multi-person households – can’t be defined as “happy and glamorous singles.” There’s a considerable income gap even in this age group, and many of them face poor housing conditions. According to data from Statistics Korea, 9.7% of single-person households in their 30s have a yearly income above 60 million won (US$53,107), while 9.3% make less than 12 million won (US$10,621) a year. While elderly single-person households are universally impoverished, there’s a distinct gap between the rich and poor among people in their 30s. Young people in their 30s are more likely to live near Seoul or other urban areas than other age groups. When young people with little income live in an urban area, they have to put up with worse housing, while paying more than they would in other areas. People facing poor housing conditions can hardly expect a high level of safety.

|

|

Current income levels for single-person households

|