|

|

Yang Il-hwa shares his thoughts on the South Korean government finally dismissing a case against him concocted during the Jeju Uprising.

|

Yang Il-hwa was imprisoned without being told what his crime had been

“I’m just so happy to be able to clear away this black mark that has been following me around for 70 years.” Tears flowed in thick streams from Yang Il-hwa’s eyes after a court ruled on Jan. 17 to dismiss indictments in a case by 18 former prisoners requesting a retrial from the state following their unjust imprisonment at the time of the Jeju Uprising and Massacre and its aftermath in 1948–49. At that moment, the “black mark” that the 89-year-old (a resident of the village of Geumak in Hallim Township, Jeju City) had lived with for over seven decades was washed away. A kaleidoscope of past events appeared before his eyes. On Nov. 20, 1948, his village on the slope was set ablaze after an eviction order by punitive forces. His parents relocated to Hallim Township, while Yang lived with his uncle’s family in Jeju Township (now Jeju City). Early that December, he was captured by chance on the street by a right-wing young men’s association. “I was beaten senseless with firewood they’d brought into the police station interrogation room to build a fire. My body was swollen, and I had no skin left,” he remembered. He spent around ten days there before being delivered for a court-martial. The soldier in charge of the proceedings would instruct individual people to stand; when they stood up, he would ask, “Did you do this or that?” If they answered “yes,” he would write their name down and order them to sit in one of two groups: the people to be sent to prison, and those to be executed. Hundreds of people were tried each day.

|

|

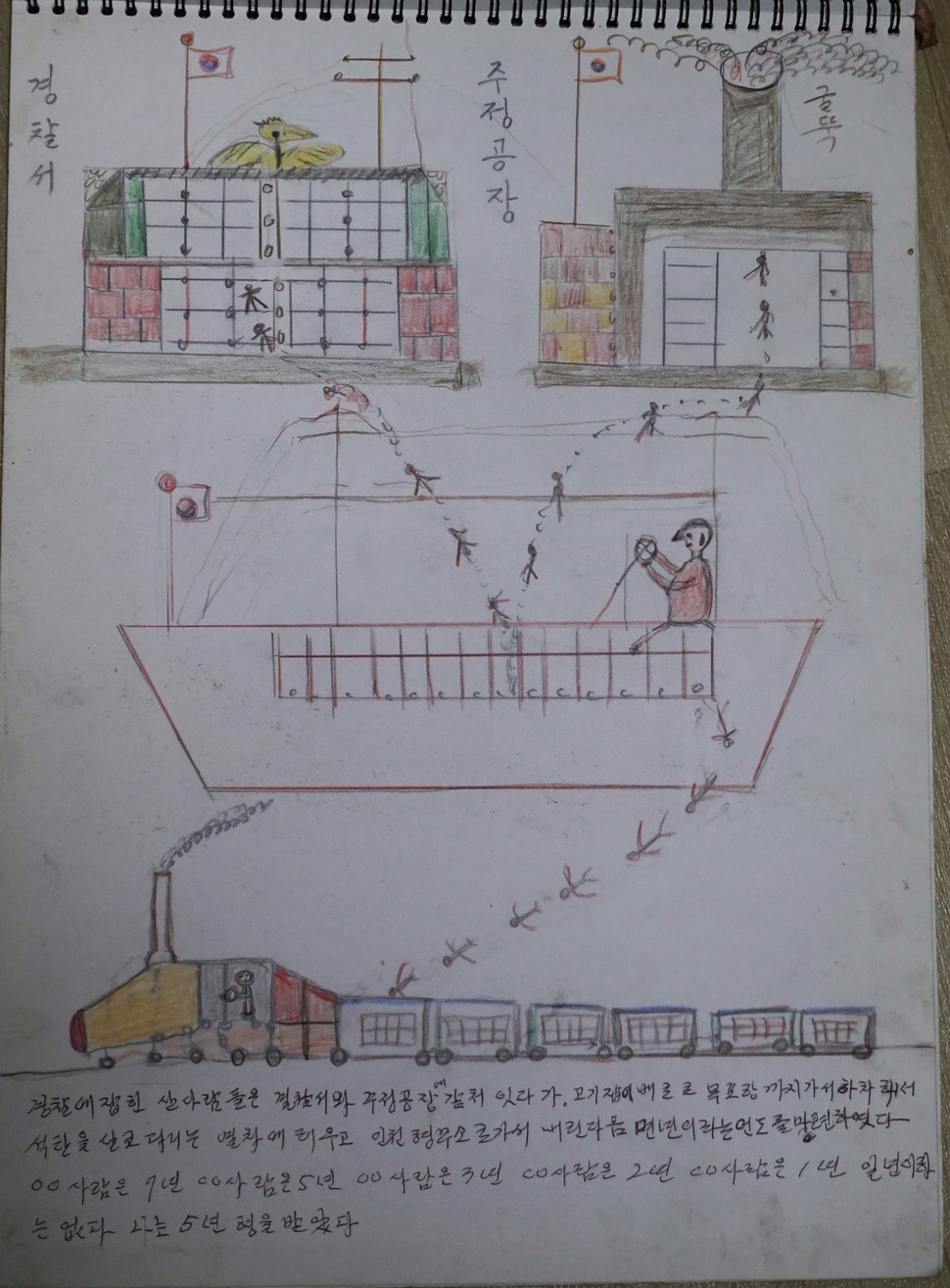

A picture drawn by Yang to illustrate the process by which he was “tried” and imprisoned.

|

|

|

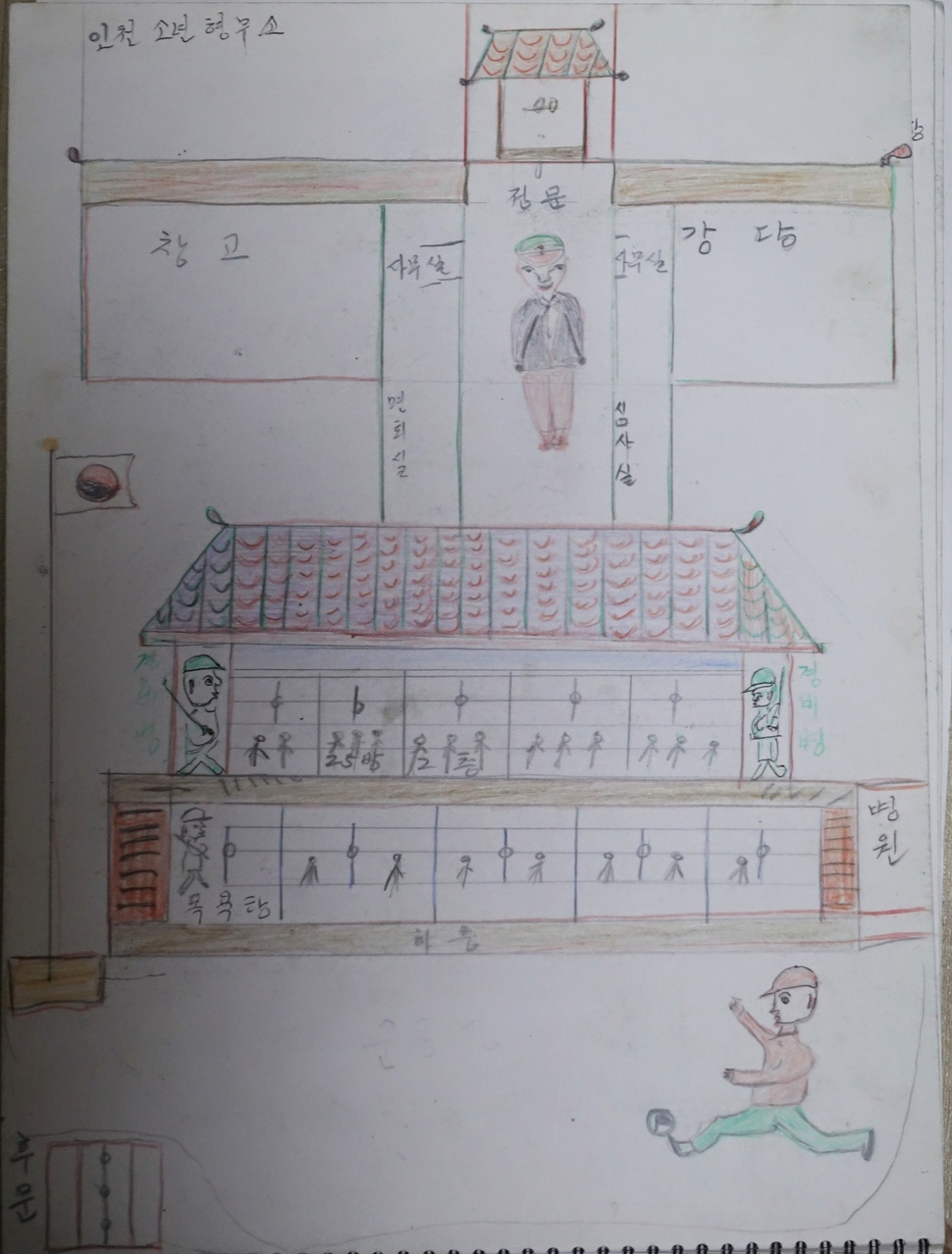

A picture drawn by Yang to illustrate his time spent in prison.

|

|

|

Yang shares his thoughts on the government’s dismissal of its case against 18 former Jeju Massacre victims who were wrongly imprisoned.

|