|

|

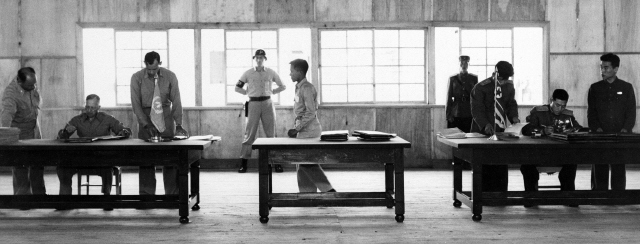

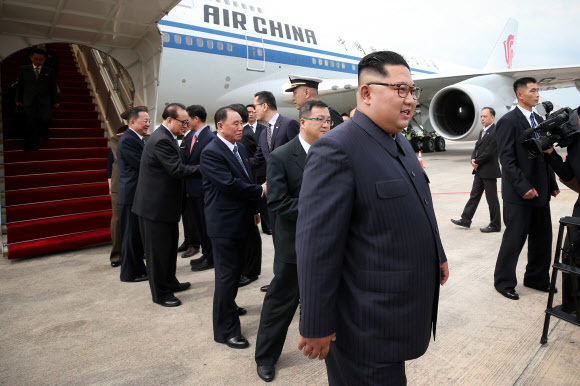

After arriving in Singapore on June 10 for the “talks of the century,” North Korean leader Kim Jong-un (left) heads to at the Istana presidential palace to meet with Singapore‘s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. US President Donald Trump greets his welcoming party after landing at Singapore’s Paya Lebar Airbase on the night of June 10. (AP and AFP, Yonhap News)

|

Even after 70 years of hostilities between North Korea and US, it is never too late for peace

“It is unknown territory in the truest sense. But I really feel confident. I feel that Kim Jong-un wants to do something great for his people, and he has that opportunity.”

Just before departing the G7 Summit host country of Canada on June 9 to attend a North Korea-US summit that is poised to decide the future of the Korean Peninsula, US President Donald Trump described the upcoming meeting between the North Korean and US leaders as “unknown territory” – something never before experienced in human history.

“You know, this has not been done before at this level [between the North Korean and American leaders],” Trump said at the press conference.

“We’re going in with a very positive spirit,” he added.

From inside the plane to Singapore, Trump tweeted a message predicting the summit date of June 12 would be “an exciting day” and sharing his “feeling that this one-time opportunity will not be wasted.”

The Associated Press (AP) reported on June 11 that Trump and Kim will meet for a one-on-one session, accompanied only by their interpreters, on the morning of June 12 for two hours. The first of the two leaders to arrive in Singapore for the “uncharted” meeting was North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. An Air China aircraft with Kim on board departed Pyongyang at 8:39 am on June 10 and touched down at Singapore’s Changi International Airport at 2:35 pm. Appearing in a people’s uniform and glasses, Kim smiled broadly as he was welcomed by Singaporean Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan. Later that evening, Kim met with Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong.

Trump arrived at Singapore’s Paya Lebar Air Base six hours later at 8:35 pm. He and Kim respectively rested from their trips at the Shangri-La Hotel and the St. Regis Singapore. After 70 years of conflict and hatred, the two leaders were staying in accommodations separated by a distance of just 570 meters.

Before the two “came together” today, the running themes between North Korea and the US have been nuclear weapons and the fears they have triggered. After an all-but-assured Korean War victory slipped away in Oct. 1950 with the arrival of Chinese Communist forces, UN forces commander Douglas MacArthur asked President Harry Truman to approve the use of 26 fully atomic bombs.

Describing North Korea’s fears at the time in his recent book “Code of the Third-Floor Secretariat,” former North Korean minister to the UK Thae Yong-ho wrote, “North Koreans thought, ‘If the US drops an atomic bomb, everyone will die.’”

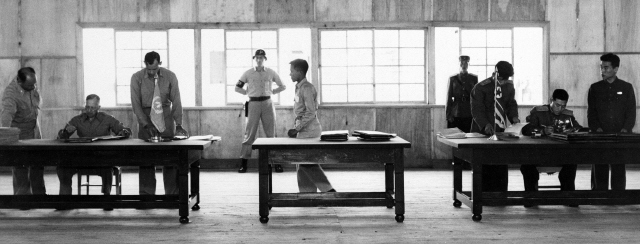

The signing ceremony for the Korean War armistice agreement on July 27, 1953, ended in 11 minutes without any handshakes, nods, or commemorative photographs between the North Korean and US sides as they left their signatures on the document. The US positioned its first nuclear warheads in South Korea in 1957; at one point, they numbered over 900.

|

|

William Kelly Harrison Jr. (far left), head of the United Nations Command armistice delegation, and North Korean General Nam Il (far right) sign their respective portions of the Korean Armistice Agreement on July 27, 1953, in Panmunjeom.

|

First opportunity: 1991 Joint Declaration of Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula

Faced with the US nuclear threat, North Korean embarked on a nuclear development program early on. In its February “Global Nuclear Landscape” report, the US Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) wrote that North Korea’s nuclear program “began in the late 1950s [soon after the Korean War] with cooperation agreements with the Soviet Union on research.”

It introduced a small research reactor (IRT-2000) in June 1963, and by 1986 it had a 5MW graphite-moderated reactor in operation that was “capable of producing about 6 kilograms (kg) of plutonium per year.” The US, for its part, threatened North Korea with B-52 bombers, aircraft carriers, and other strategic assets whenever a crisis occurred, such as the USS Pueblo’s capture in 1968 or the Panmunjeom axe murder incident in 1976.

Eventually, the Cold War came to an end. For North Korea, this was both a crisis and an opportunity. In Sept. 1990, Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze visited Pyongyang and gave notice of the Soviet Union’s plans to establish diplomatic ties with South Korea. Enraged, North Korean Foreign Minister Kim Yong-nam warned that the North would “no longer be bound by the promise not to develop the weapons we desire.” Pyongyang’s message was that after the Soviets’ betrayal, it would embark on its own nuclear development program.

There were opportunities, to be sure. On Sept. 27, 1991, US President George H. W. Bush announced the withdrawal of land- and sea-based strategic nuclear weapons from US military bases around the world. The following Dec. 18, South Korean President Roh Tae-woo declared, “As of this moment, there is not a single nuclear weapon anywhere in the Republic of Korea.”

On Dec. 31, South and North signed a Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, in which they agreed “not to test, manufacture, produce, receive, possess, store, deploy, or use nuclear weapons; [. . .] not to possess facilities for nuclear reprocessing and uranium enrichment; [and to] conduct inspections of locations chosen by the other side and mutually agreed upon by both sides.”

|

|

North Korea’s official newspaper, the Rodong Sinmun, dedicated the front page of its June 11 edition, to covering the farewell ceremony for North Korean leader Kim Jong-un before his departure to Singapore from Pyongyang International Airport on June 10. (Rodong Sinmun webpage)

|

Second opportunity: 1994 Agreed Framework in Geneva

In Jan. 1992, North Korea signed an International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) nuclear safeguards agreement. But in Mar. 1993, it declared its withdrawal from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in protest of the IAEA’s demands for “special inspections.” The US considered a strike against Yongbyon – home to most of North Korea’s nuclear facilities – but abandoned its plans after predictions projected losses of 50,000 US troops, 490,000 South Korean troops, and over one million civilians within three months of opening hostilities.

It was a touch-and-go situation for the Korean Peninsula, until former President Jimmy Carter came to the rescue. Carter met with North Korean leader Kim Il-sung and received a promise from him to freeze nuclear development and participate in an inter-Korean summit. By Oct. 1994, North Korea and the US had reached their Agreed Framework in Geneva, where the US would build a light-water reactor in the North, which would freeze its nuclear program in return.

After that came the missile crisis. On Aug. 31, 1998, North Korea launched its first long-range ballistic missile, the Taepodong-1. That November, President Bill Clinton tapped former Secretary of Defense and North Korea hardliner William Perry to serve as North Korea policy coordinator.

Former South Korean Minister of Unification Lim Dong-won – architect of the “Sunshine Policy” – managed to win Perry over. In Oct. 1999, a report was completed with the outline of an engagement policy in which North Korea would be persuaded to implement a full-scale halt of its nuclear and missile development plan, ultimately bringing the Cold War on the Korean Peninsula to an end.

A historical reconciliation between North Korea and the US seemed within reach. A first meeting of the two sides’ foreign ministers took place in late July 2000 at the ASEAN Regional Forum in Bangkok. National Defense Commission first vice chairman Cho Myong-rok visited the US the following Oct. 10 and met with Clinton at the White House.

The following day, the two sides issued a joint communiqué pledging to “make every effort in the future to build a new relationship free from past enmity.” Secretary of State Madeleine Albright arrived in Pyongyang on Oct. 23 for a three-day return visit. It was the same time that the North Korea-US summit had originally been scheduled to take place.

|

|

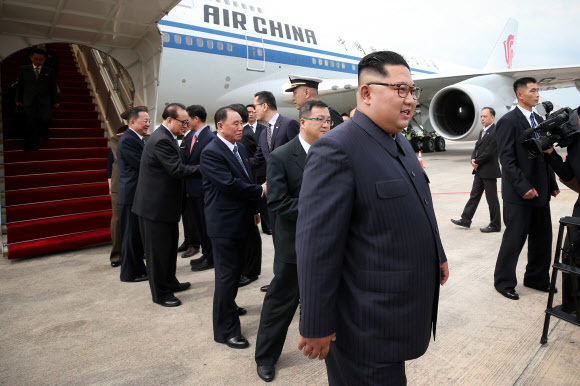

A car assumedly transporting North Korean leader Kim Jong-un heads to Kim’s accommodations at the St. Regis Singapore hotel on June 10 (Kim Seong-gwang, staff photographer)

|

Third opportunity: Clinton’s planned 2000 Pyongyang visit, but failed

There were no further miracles. Clinton canceled his planned Pyongyang visit after neocon-anointed George W. Bush was elected President of the US in Nov. 2000. Following the 9/11 terrorist attacks of 2001, Bush delivered a Jan. 2002 State of the Union address declaring Iraq, Iran, and North Korea as forming an “Axis of Evil.” During a Pyongyang visit that October by assistant US secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs James Kelly, North Korean first vice foreign minister Kang Sok-ju asserted that North Korea was “entitled to possess” nuclear capabilities, or “even more powerful” ones.

The US interpreted this as acknowledgment of a plan for development of nuclear weapons with highly enriched uranium and backed out of the Agreed Framework. In protest, North Korea moved in Jan. 2003 to once again declare its withdrawal from the NPT. Subsequent efforts to resolve the nuclear issue through the Six-Party Talks proved unsuccessful. Bush’s successor as President, Barack Obama, eschewed dialogue with Pyongyang as part of a policy of “strategic patience.”

In the meantime, North Korea declared itself a nuclear power in its Constitution in May 2012 and adopted a two-track approach of simultaneous nuclear and economic development in Mar. 2013. It conducted six nuclear tests, and its Nov. 2017 test-launch of the Hwasong-15 missile showed it had made considerable progress on gaining the capabilities for an ICBM strike on Washington, DC.

|

|

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un and his aides arrive on June 10 at Singapore’s Changi Airport, where they were greeted by Singaporean foreign minister Vivian Balakrishnan. (provided by Singapore’s Ministry of Communications and Information)

|

The next 18 years

Over the past 70 years, relations between North Korea and the US have been marked by enmity and distrust, feeble rays of hope undone by major disappointments. On June 12, Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un will be taking their first steps into “unknown territory” that could potentially bring permanent peace to the Korean Peninsula. On June 9, Trump said the meeting “should have been done five years ago and 10 years ago and 25 years ago.” But when it comes to take a bold first step toward peace, there is no such thing as “too late.”

By Gil Yun-hyung, Hwang Joon-bum, Kim Ji-eun and Noh Ji-won, staff reporters