|

|

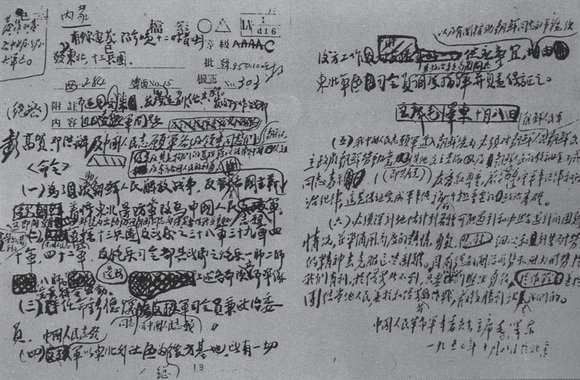

A document dated to Oct. 8, 1950, written in the hand of Mao Zedong, orders Chinese military leaders, including Peng Dehuai, Gao Gang and Hong Xuezhi, to send troops to the Korean War. Mao originally wrote “支援軍,” meaning “supportive army,” but revised it to “志願軍, or “volunteer army,” in four of the six places where the team appears.

|

Mao Zedong refers to troops sent to Korea as “volunteer army” in 1950 document

On Oct. 8, 1950, a document handwritten by Mao Zedong was sent to the leaders of China’s military, including Peng Dehuai, Gao Gang and Hong Xuezhi, ordering them to send troops to the Korean War. An early draft of this document contains numerous traces of revision. One interesting change was in the name of the army that was sent to Korea, called the People’s Volunteer Army (PVA). Mao originally wrote “支援軍,” meaning “supportive army,” but replaced that with “志願軍,” meaning “volunteer army. The two words are homonyms, with the basic pronunciation of “zhiyuanjun,” though the tones are different. Considering that this correction was made in four of the six places where the word “volunteer army” appears, it doesn’t appear to have been merely an accident. This document was featured in an exhibition in Beijing on June 2011, on the 90th anniversary of the Communist Party of China (CPC). Chinese newspapers that covered the story of the exhibition reported on the reason the name had been changed. Mao and the Communist Party had originally wanted the name of the army to reflect the fact that China was helping North Korea on a governmental level, but the name was changed after Huang Yanpei, one of China’s founding fathers and a member of the China Democratic League (rather than the Communist Party), argued that this was inappropriate. Hwang suggested that the army should have a non-governmental quality since the US might declare war on China if China supported North Korea with its regular army. In light of this background, finding the homonym “志願” was a stroke of genius. There is a rival theory that the troops were voluntary to begin with and that the name was never changed, but the idea that Huang suggested the name change is widespread in China. Whatever the case, even though China’s supreme leader Mao Zedong appointed Peng Dehuai as commander and ordered him to swiftly reorganize the regular troops on the northeastern border into the “People’s Volunteer Army” and send them into battle, China effectively claimed that people were going to war on a voluntary and individual basis rather than on the orders of the state. China also claimed that the PVA was not a state army during the debate about withdrawing foreign militaries that was repeatedly brought up during the negotiations about ending the Korean War. If the UN forces withdrew, the Chinese said, they would do their best to persuade the PVA to go home, too. Peng Dehuai even signed the armistice agreement on July 27, 1953, as “commander of the People’s Volunteer Army.” When the PVA withdrew from North Korea in 1958, they were absorbed into the Chinese regular army. Though there was a continuing debate about how these soldiers were treated, there were no more actions taken under the name of the PVA command. That was because, at least officially, this volunteer organization had dispersed. While announcing its intention to take part in building a peace system on the Korean Peninsula, China has brought up its status as a signatory to the armistice agreement. But if we take the PVA’s identity seriously, China explicitly forfeited its status as a belligerent from the very beginning of the war. For China to now claim that the state participated in the war could raise the controversy about “interfering in domestic affairs” that it had initially feared. This also contradicts the position that China frequently emphasizes these days about never interfering in other country’s domestic affairs. China’s concerns are also evident in the Sino-North Korean Mutual Aid and Cooperation Friendship Treaty, which was concluded in 1961. The second clause of the treaty promises automatic engagement if either side is invaded, which certainly sounds like a military alliance. But China later adopted the position that it had forged a partnership, not an alliance, and has criticized the US’ alliances with South Korea and Japan and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) as relics of the Cold War. China no longer speaks openly about its alliance with North Korea, and it would be awkward to do so. Though China’s status as a party to the Korean War and its alliance with North Korea are key issues related to the end-of-war declaration and the conversion to a peace regime, China’s unclear position has become an obstacle in various respects. But this is also a topic that China is unlikely to bring up on its own. Perhaps it would be best for South Korea to officially recognize China’s status as a party to the armistice, the end-of-war declaration and the peace regime while simultaneously emphasizing that the China-North Korea alliance provides balance to the South Korea-US alliance. By Kim Oi-hyun, Beijing correspondent Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]